Born in Barnsley in 1923, Harry remembers the terrible poverty as a child

The activist and war hero fears we are going back to a worse time but tells Ros Wynne-Jones he still has hope

Inside Hoyland Working Men’s club, Harry Leslie Smith is talking about his childhood in the town, close to Barnsley.

“It was a terrible experience for a young child,” says Harry, now a 95-year-old writer and activist.

“We lived in slums and dosshouses. Most evenings my sister and I would go to bed with growling stomachs and no supper.”

For the past 18 months we have been retracing George Orwell’s ‘Road to Wigan Pier’, telling the stories we have found along Orwell’s route in the Daily Mirror. Barnsley was Orwell’s last stop. And the places he describes so vividly in his iconic book were the homes Harry lived in throughout his childhood, after his father was injured in a mining accident.

On Orwell’s 115th birthday we are launching a multimedia interactive story of that trip – wiganpierproject.com. It’s also the second anniversary of Brexit, where people in hard-pressed towns like Barnsley voted 68 per cent to Leave.

And it is the eighth anniversary of David Cameron and George Osborne announcing the ‘Age of Austerity’, the moment gains for working class people went into their steepest decline since the second world war. “After my childhood, things improved,” Harry says. “But now I fear we are going back to those times.”

The Gawber Pit that Orwell went down closed in 1988, and the new mines are warehouses shut off from the sky. The town’s biggest employer is ASOS.

Joanne Goddard, 24, worked for the clothing company as a £7.55-an-hour picker at their distribution centre in Grimethorpe until she says she was sacked after collapsing with stress.

Her husband Joe Beckett, 27, worked the night shift. Both worked via an agency called Transline, later sacked by ASOS. “You’re nothing to them, it’s slave labour,” Joe says. “One time I rang in to let them know I was going to be off because our daughter was in hospital with an appendicitis and the manager told me he needed a picture of my daughter in hospital as proof. So I had to take a photo of my sick child, lying in bed, and send it in.

“We had a miscarriage and their reaction was the same. They wanted proof. I’m not sure what they wanted me to show them really. Why would anyone lie about something like that? They said ‘fine we’ll let you know if you’re needed again’ - basically threatening me with the sack three days before Christmas.

The place where these men and those loading the broken coal on to the tubs were working was like hell. I had never thought of it before but of course as the machine works it sends forth clouds of coal dust which almost stifle one and make it impossible to see more than a few feet. No lamps, except Davy lamps of an old-fashioned pattern, not more than two or three candle power, and it puzzled one to see how these men can see to work, except when there are a number of them together. To get from one part of the coalface to another you had to crawl along awful tunnels cut through the coal, a yard high by two feet wide, and then to work yourself on your bottom over mountainous boulders of coal. Of course in doing this I dropped my lamp and it went out.

Orwell’s diary entry for Barnsley, The Road to Wigan Pier

“Then I get a text saying I was AWOL - even though I’d called and texted. When I went back they said, ‘you’re a man, why do you need time off? And we need a doctor’s note’. As if I’m going to send Joanne to a doctor at that time. It’s ludicrous.

“They’re heartless. They want robots not humans. I still went back. I agreed to work Christmas Day night because it was triple pay. No-one wants to miss out on Christmas with the family, especially after the miscarriage, but we needed the money so I agreed to do it.

“We had Christmas morning then I went to bed in the afternoon, missing out on time with Joanne and the kids, so I’d be ready to work through the night. When we got paid in January the extra money wasn’t there. They said that because I’d been off for the miscarriage I wasn’t entitled to the extra pay.”

In one of our other stories, Arron Baldwin, 25, from Barnsley, who worked at ASOS for four years, says working at the company made him into a “ youthful, optimistic proud individual into a clinically depressed, demotivated and pessimistic mess.” ASOS declined to comment on all these stories.

Harry was born in Barnsley in 1923, his crib a drawer in a dresser, 13 years before Orwell came to the town to interview miners. Now, he is lost in the memory of how his mother would send him, aged five, and his sister Marion, aged three, out find scraps of coal. “My sister and I would climb up the slagheaps and dig through to find some tiny scraps to give us a fire that night,” Harry remembers. “I can see the look on my father’s face when we couldn’t find any.”

Marion died in the workhouse infirmary of tuberculosis at the age of 10 because Harry’s parents couldn’t afford the doctor. The site of the pauper’s pit where she was buried in 1926 now lies unmarked beneath Barnsley Hospital – where the NHS now treats TB patients thanks to the legacy of Harry’s generation.

Harry remembers “tramping to school and my stomach was giving me so much pain that all I could think of was the small glass of milk waiting at school for children like me.” Yet in Barnsley in the winter of 2018, we find children still facing the physical pain of hunger. In the 800-year-old market, the Rose Vouchers for Fruit and Veg Project is helping families on low incomes buy fresh food. A little girl in a pushchair smiles delightedly as she shoves a banana bought with a voucher happily into her mouth.

When Orwell reached Barnsley, he stayed with a miner, Albert Gray, at Agnes Terrace. His diary recorded “Two little girls, Doreen and Ireen (spelling?) aged 11 and 10.” Albert’s grandson Dave tells us: “My mum Irene was 10 when Orwell came to stay.”

Today, Dave rents out the house, living nearby in a bungalow where his dad’s kerosene miner’s lamp is kept proudly on display. “We were all miners on this street,” Dave says. “My dad started at 14 and worked for 45 years. I started at 22 and it was my dad who trained me.” With mining gone, Dave now works in a bakery.

The home’s current tenants are George, 39 and his wife Flori, 46, both from Bucharest. As we chat, George leaves for his shift at a local factory where he’s on a zero hours contract.

In nearby Hoyland, where Harry began his long life, the slum where he lived has long been demolished, but we find his grandmother’s old terrace. New owner Margaret Fletcher, 45, lets us stand in the garden amongst Harry’s ghosts.

“These houses weren’t really homes, when I lived here,” Harry says. “They were just places for workers to rest between gruelling shifts at the pit. The country was run by the people who owned the mines, and the ordinary worker wasn’t seen as a human being. He was an asset used by the companies to further their wealthy nests. With places like ASOS I have a terrible feeling we are going backwards.”

He looks up at the sky. “But I still have hope. People have an inner strength that drives us to survive.”

After a year’s journey across the UK, through foodbanks, homeless shelters, freezing, damp homes, advice centres, bus stops, parks and shopping centres, Harry sums up our modern-day Road to Wigan Pier. Decades of post-industrial decline – turbo-charged during the brutal Tory austerity years since 2010 – mean deep poverty has resurfaced all through Britain’s former industrial heartlands. But today that road is not just tarmaced with the sweat of previous generations but also paved with their hope.

And somehow, 95 years after being born into Orwell’s bitter Barnsley, Harry – a living path not just to but from Wigan Pier – still has enough hope for all of us.

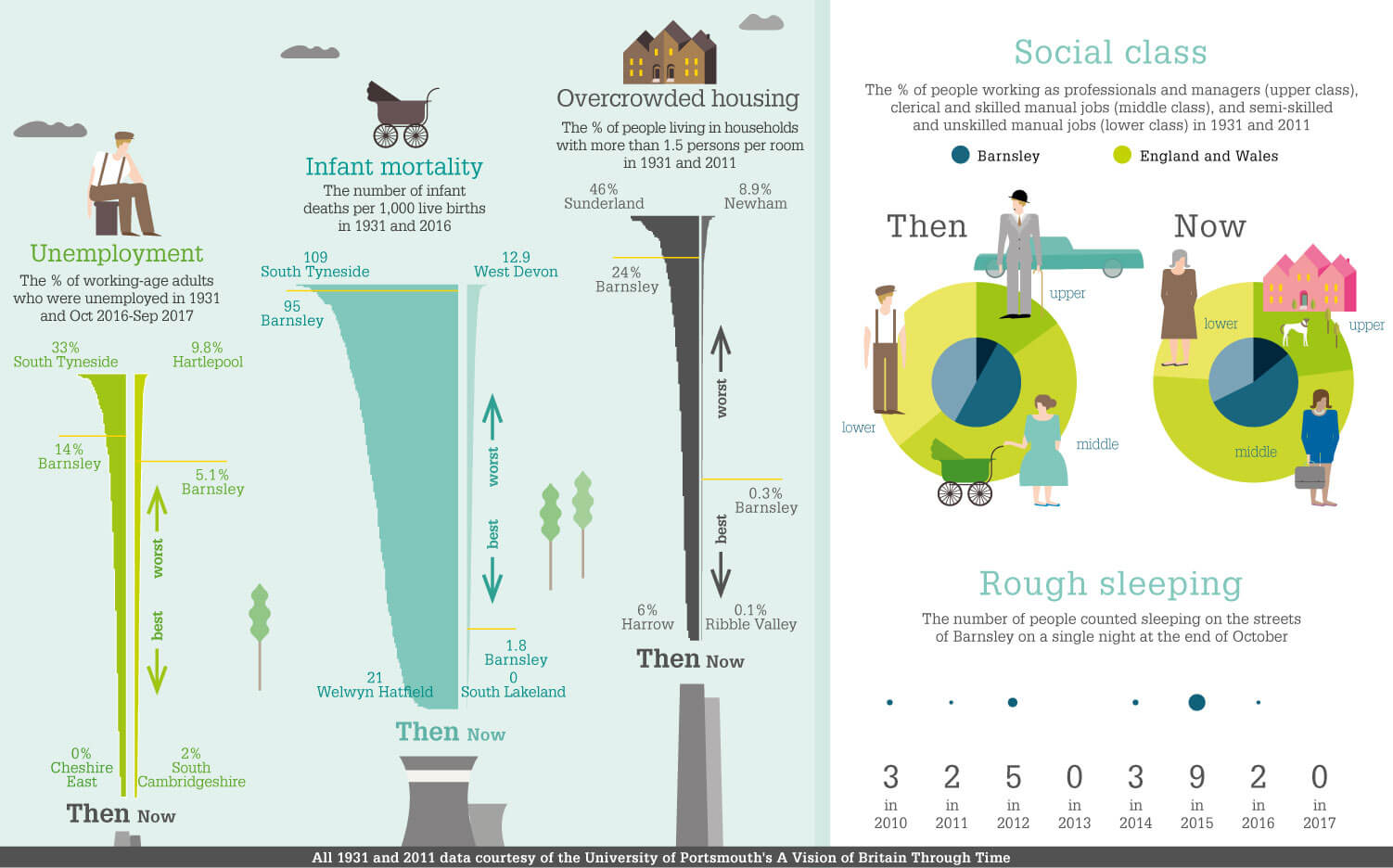

What the numbers say

Your story

If you live in any of the places mentioned in the Wigan Pier Project and have a story to share, please get in touch.

You can contact us via wiganpier2017@mirror.co.uk tweet us at @WiganPier80 or write to Wigan Pier Project, Daily Mirror, One Canada Square, Canary Wharf, London E14 5AP

From the archives

Fascinating photographs from the Mirror archives showing what Barnsley looked like when Orwell visited

For housing advice

For housing advice

For general advice

For general advice

For foodbank help

For foodbank help

For help in work or out of work

For help in work or out of work