Life on the streets for a new generation of homeless people

Ros Wynne-Jones hears of the heartbreak of poverty in Leeds and finds out how people are fighting back with their 'humanifesto'

Until recently, visitors to St George’s Crypt, a homeless project in the heart of Leeds, were greeted by a 6ft 7in former bare-knuckle boxer.

“I lost my first three teeth from my dad,” he says, matter of factly. “When I were 15, my mum went into a nervous breakdown from my dad’s violence and tried to suffocate me with a pillow. I remember waking up in the pitch blackness fighting to breathe. I left home that day. When I grew up all I wanted to do were fight.”

The 47-year-old Yorkshireman told us he moved to London with a friend but three weeks later his pal died of a heroin overdose. For the next 12 years he lived in the homeless metropolis under Waterloo station known as Cardboard City. His fear of needles kept him from heroin. “My poison,” he says, “was a can of Special Brew mixed with cherry brandy.”

When we met him, he was the teetotal warden or doorman at St George’s, a job for which he seemed perfectly suited. Years of violent battery had shattered and delivered a blood clot to his brain but also made him an invaluable member of staff at the crypt. “If I can do it, you can,” he told new arrivals.

But a few weeks later he was gone.

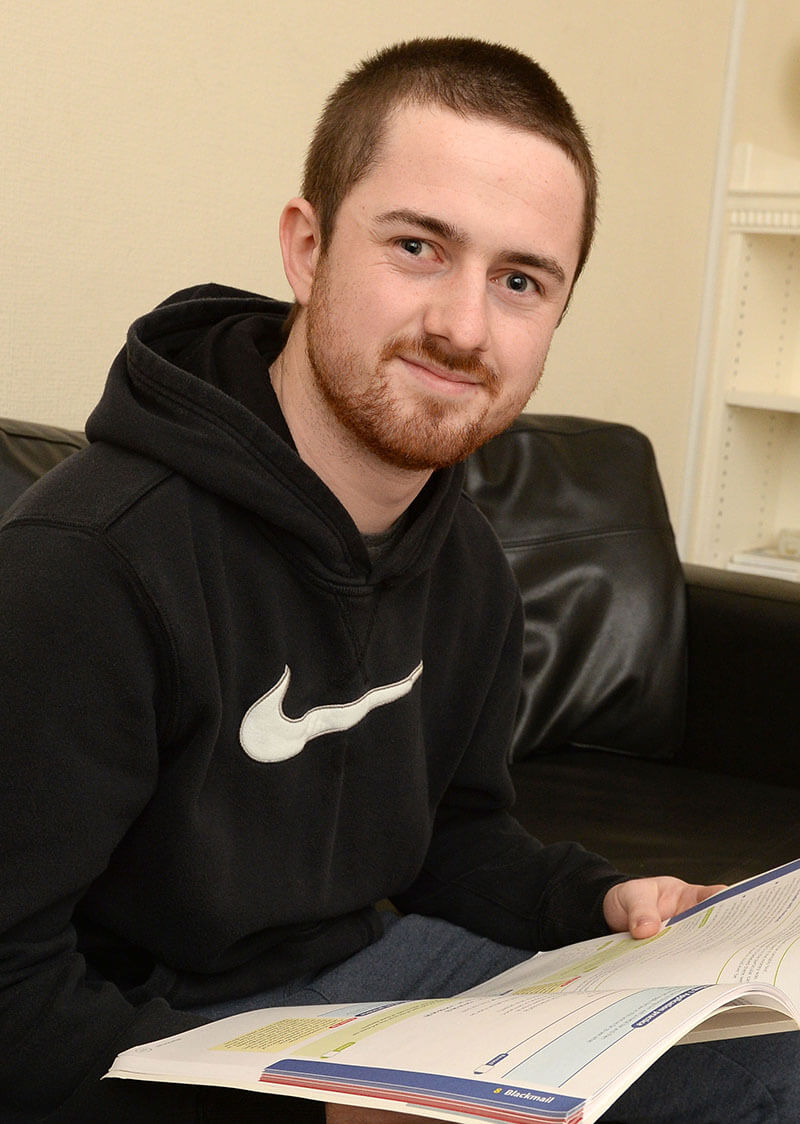

Leeds is the penultimate stop of our Wigan Pier Project, retracing George Orwell’s steps through the north of England 80 years on. Our visit to the crypt comes to be defined by two men – the bare-knuckle boxer whose life could come straight from the pages of Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London, and Lee, a softly spoken builder, who is part of the new generation of homeless people returning to our streets.

Lee has always been in steady work and secure housing. He has no addictions or mental-health problems. But at 50, his building firm got into difficulties.

“The industry went flat,” he says. “It’s picking up now a bit. But for a while there were suddenly no extensions or new builds. We didn’t get paid for some of the work we’d done. I got into financial difficulties and very suddenly my house got repossessed.”

Lee’s parents had both died. “I stayed with a few friends but you can’t keep putting on people,” he says. “In the end I’d used up every favour. I felt I was lost.”

One night he found himself with no sofas left to surf.

“I decided to try and find a place to sleep near the Jobcentre so I could look for work,” he says.

“I went to a bar that had closed down. It had some steps below street level so I lay down there. It had a broken sign that I pulled over the top of me so no one could really see me. It was the worst four days of my life.”

He found a day centre offering washing facilities which referred him to St George’s Crypt where he was able to get proper help, eventually moving into a shared home.

“I volunteer here now,” he says. “It’s the least I could do.”

Orwell made two visits to Leeds to write about poverty. The first was in 1930 when he was writing Down and Out in Paris and London and stayed with his sister, Marjorie, and her husband Humphrey Dakin, a civil servant. The second was in 1936, researching Wigan Pier. He also made a pilgrimage to Haworth Parsonage to see Charlotte Bronte’s “cloth-topped boots”.

Dakin had little time for Eric Blair – Orwell’s real name – or his threadbare overcoat, lack of a hat and the constant clack-clack of his typewriter at the kitchen table.

On Orwell’s first visit the Dakins lived in Bramley, where St George’s Crypt now runs a satellite project just a few hundred yards away.

Local Labour MP Rachel Reeves says: “Of course Leeds has changed beyond compare since Orwell’s day but housing is still the main thing people come to the surgery with.

“People are still desperately seeking decent, affordable homes and are battling with low pay and cuts to support.”

Opposite her surgery is the building where Dakin’s local, the Cardigan Arms, stood. Now it has been turned into flats.

“I tried to get Eric to come to our pub,” Dakin remembered of his 1930 visit.

“Even in those years in the slump it was always bright, cosy and warm, with a big fire going and quite a merry crowd in the evenings. From time to time I managed to persuade Eric to come along but I could never make him join in any game or conversation. He used to sit in a corner by himself, looking like death, until it was with some relief we’d hear him say, ‘I must go home.’ Later Dakin claimed the landlord told him, “Don’t bring that b****r in here again.”

By Orwell’s second visit, the Dakins were living in Estcourt Avenue, within sight of today's floodlights at Headingley. Now the cardboard cut-out of Will Smith in the house window hints at students in residence and its landlord’s story tells a tale of changing times.

Russell Cameron, 53, bought the house 15 years ago with the payout from an industrial accident at a chemical factory where he suffered burns.

Staying till next Wed with M[arjorie] and H[umphrey] at 21 Estcourt Avenue, Headingley. Conscious all the while of difference in atmosphere between middle-class home even of this kind and working-class home. The essential difference is that here there is elbow room, in spite of there being 5 adults and 3 children, besides animals, at present in the house. The children make peace and quiet difficult but if you definitely want to be alone you can be so – in a working-class house never, either by night or day.

Orwell in his diary entry for Leeds, The Road to Wigan Pier

Inside, the coal fire has been replaced by a large flat-screen TV and games console. Kyle Newbould, 20, the son of a taxi driver and cleaner from Harrogate, North Yorks, is studying at the university to be a sports therapist. He estimates he’ll leave the course with £60,000 of debt. “It’s a lot of money, so much you almost can’t get your head round it,” he says.

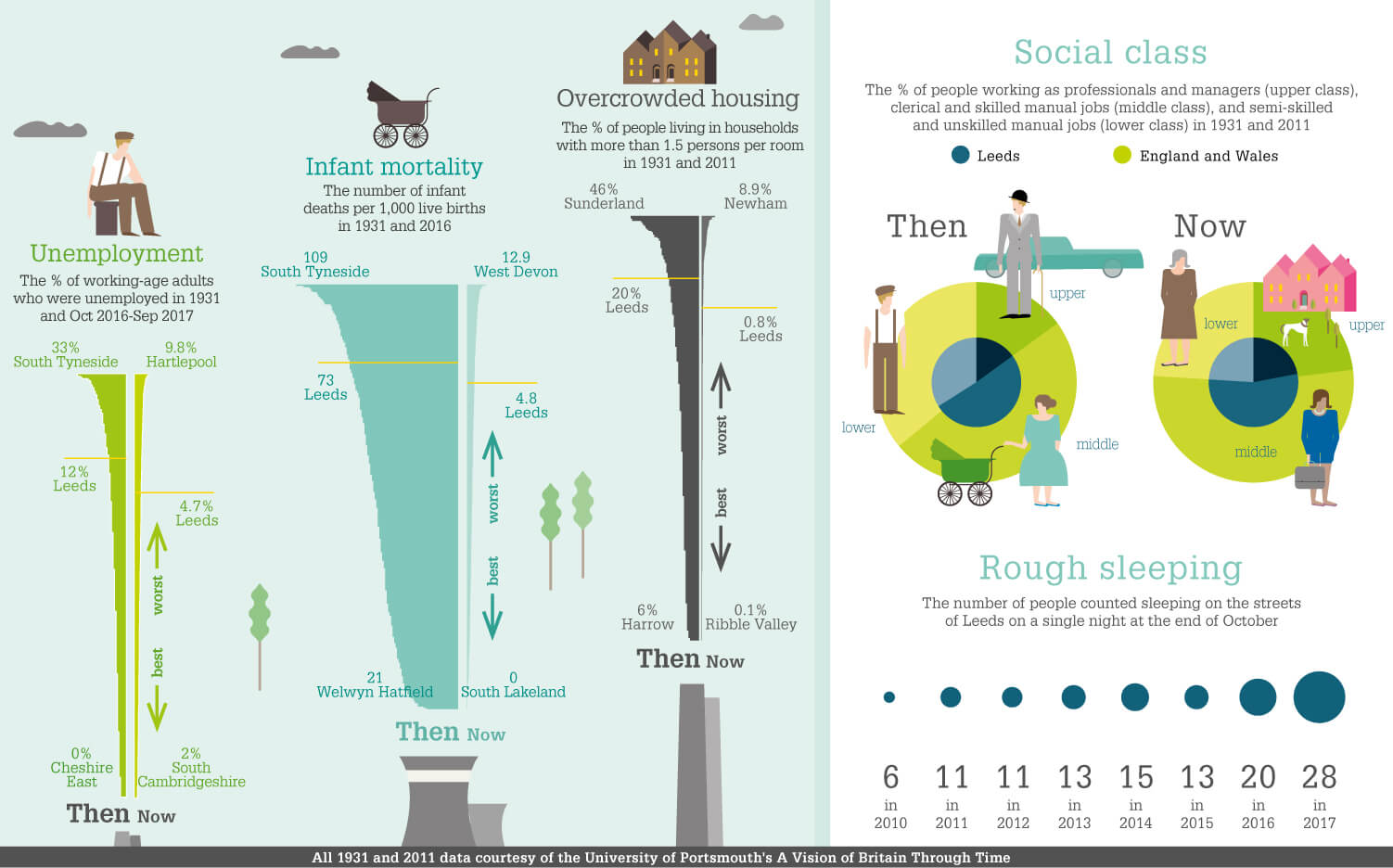

Last year the number of rough sleepers in Yorkshire and the Humber rose 139%

When Orwell first visited in 1930, the crypt at St George’s had just been opened to help a tide of homeless people, many of whom had fought in the First World War and were washed up on Leeds streets by the Depression. Young, charismatic vicar Percy Donald Robins – known as Don – opened the crypt himself. “The first £3 ever raised for the crypt was spent on canvas to cover the coffins and gaping holes,” says Andrew Omond, who works at St George’s. “Members of the congregation brought milk, sugar and cocoa. Men poured in.”

In 2018, the number of homeless people is growing again. Last year the number of rough sleepers in Yorkshire and the Humber increased by 139%.

When all is said and done, the most important thing is that people shall live in decent houses and not in pigsties. I have seen too much of slums to go into Chestertonian raptures about them. A place where the children can breathe clean air and women have a few conveniences to save them from drudgery and a man has a bit of garden to dig in must be better than the stinking back streets of Leeds and Sheffield. On balance, the corporation estates are better than the slums but only by a small margin.

Orwell on Leeds, The Road to Wigan Pier

But in Leeds there is also a growing passion to change the narrative on poverty. Some 80 years ago, poor and working-class people relied on people like Orwell – a writer who, however well intentioned, had gone to Eton and grown up in colonial Burma – to write their story. Today, movements like the Truth Poverty Commission enable people to tell their own stories, which is part of the aim of our Wigan Pier Project.

In February, more than 150 people came to Leeds City Museum to hear 30 people – known as commissioners – launch their ‘humanifesto’ and share their personal experiences.

“Poverty dehumanises,” Amina Weston, 23, told a packed audience. “It’s not just the constant struggle to buy enough food to feed the kids or having to walk everywhere because you don’t have the bus fare, it’s about paying more for your electric and gas because you don’t have the credit history for direct debit.”

Amina told us how she’d been forced to give up studying for a degree when her family were evicted from their rented accommodation when she was three months pregnant. She and her husband and little daughter Aria have since found a new, affordable home – and now she and her sister are setting up Education Aid, providing school uniforms for low-income families.

“It isn’t right that families can’t afford to provide uniforms,” she says. “And we don’t want children to be left out or miss school because of that.”

Now, 80 years after Orwell’s visit, the humanifesto concludes: “What really grinds you down is the way other people perceive you… Any society is weaker when some of its members are excluded. Poverty dehumanises us all.”

What the numbers say

Your story

If you live in any of the places mentioned in the Wigan Pier Project and have a story to share, please get in touch.

You can contact us via wiganpier2017@mirror.co.uk tweet us at @WiganPier80 or write to Wigan Pier Project, Daily Mirror, One Canada Square, Canary Wharf, London E14 5AP

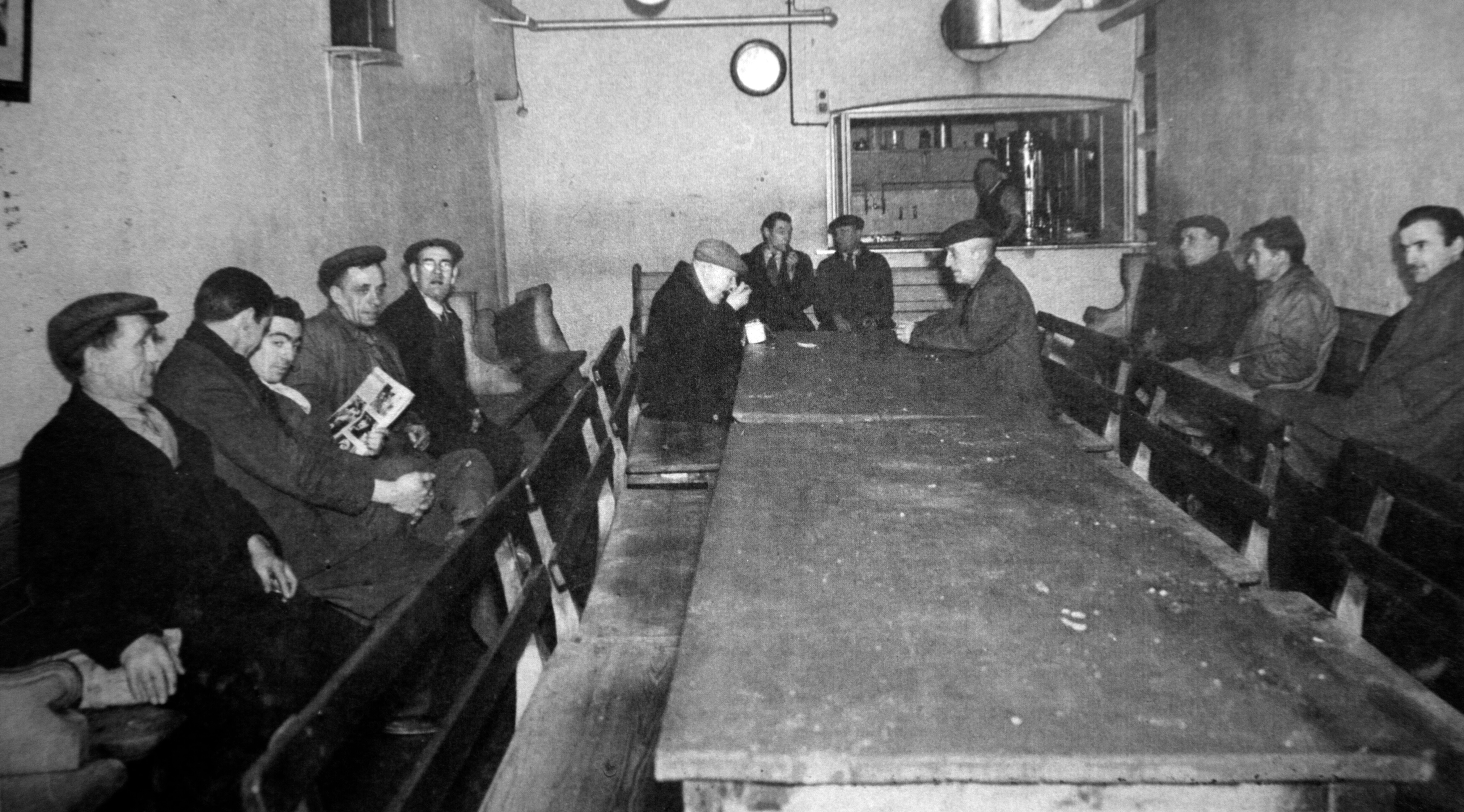

From the archives

Fascinating photographs from the Mirror archives showing what Leeds looked like when Orwell visited

For housing advice

For housing advice

For general advice

For general advice

For foodbank help

For foodbank help

For help in work or out of work

For help in work or out of work