How the heart is being ripped out of some of the poorest areas of the Black Country and Clent Hills

Meet the people who are choosing between libraries and basic care on the second part of our Wigan Pier journey

Melanie Powell and Wendy Richards are pointing at the empty shell of the NHS building behind them. “My life was saved up on that floor,” Melanie says, peering inside the worn woodwork of the windows. “Mine too,” Wendy says. “It means everything to me, this place.” They add almost at the same moment: “It means life.”

Melanie, 49, and Wendy, 48, have severe mental-health problems that at different times have caused them to attempt suicide. The Broadway North Centre in Walsall was a sanctuary. “There used to be 10 crisis beds you could come and use when you got really bad,” says Melanie, who suffers from a schizophrenic disorder. “You knew you were safe then.”

The beds were closed after council cuts in 2012. “Now even the day centre is under consultation,” Melanie says. “It’s going to cost lives. But they just keep cutting.”

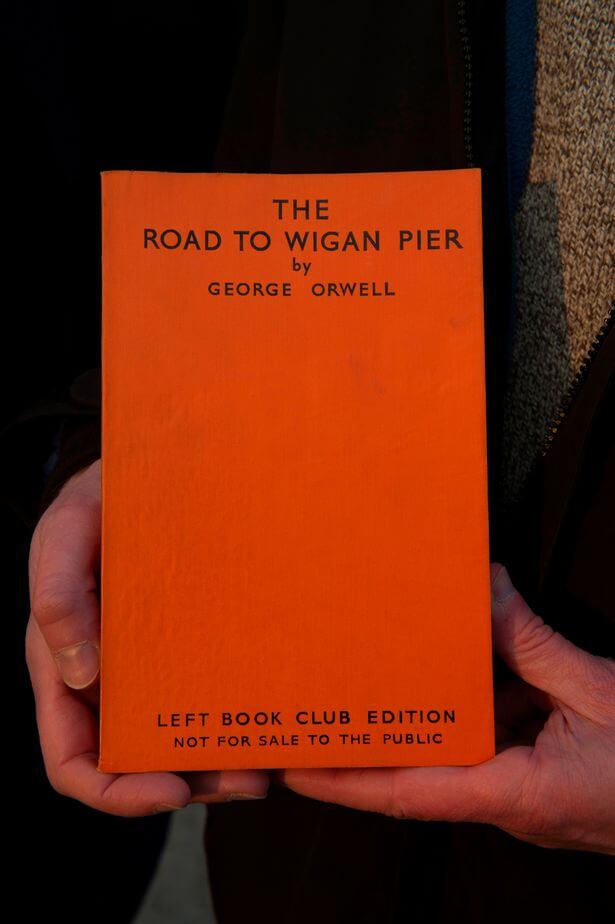

Exactly 80 years after George Orwell published The Road to Wigan Pier, we are recreating his journey, stopping where he stopped and listening where he listened. This is the second leg – Stourbridge and the Clent Hills then the Black Country.

Two miles from the Broadway North Centre, across the worn West Midlands town, shuttered-up Pleck Library is announcing its closure. Saved from the last round of cuts, it will now close altogether, taking with it the Over-50s Club, the Gujarati Reading Group, Work Club, Cradle Club and Chatterbooks – a network of community lifelines extinguished.

Walsall council has announced nine out of 16 libraries are to close, an act of cultural vandalism presented as a victory for campaigners. The original proposal had been to close 15.

Campaigner Martin Lynch says: “They are ripping the heart out of some of the poorest areas in the town.” The council says it is being forced to save £86million over four years and that without cuts and closures it would have to raise council tax 35%.

Walked 4 – 5 miles to Clent Youth Hostel. Red soil everywhere. Birds courting a little, cock chaffinches and bullfinches very bright and cock partridge making a mating call. Except for village of Meriden, hardly a decent house between Coventry and Birmingham. West of Birmingham the usual villa-civilization creeping out over the hills. Raining all day, on and off.

Orwell in his diary entry for the Clent Hills, The Road to Wigan Pier

When the future author of 1984 and Animal Farm came here, the Midlands were booming. But for Orwell, travelling north, hints of poverty and depression start in the “slummy parts” of Wolverhampton. “A frightful place,” his diary records. “Everywhere vistas of mean little houses still enveloped in drifting smoke.”

The air is cleaner today than in Orwell’s time, but still responsible for 155 excess deaths in Walsall and 139 in Wolverhampton last year, according to Public Health England.

The Black Country stopped listening to league tables in 2010 when the Lonely Planet surreally listed Wolverhampton as one of the “worst five cities” on the planet. But, however brave and resilient its people, no community can survive being cut repeatedly to the bone.

After cut upon cut, Walsall was already the fourth most deprived town in England. Yet it has now been told by central government to cut its remaining budget in half.

This means shuttered-up libraries and crippling cuts to social care delivered by a Labour council. The small town vented its rage and despair in the EU referendum, when the area voted overwhelmingly to Leave. “When nothing’s working for you, you want change,” we heard again and again.

At Walsall’s central library there are no books with Orwell’s name on the spine but there are librarians. A mum in her 70s tells me closing libraries is the right decision. “My son has learning disabilities, autism, challenging behaviour, a heart condition,” she says. “He has lost so much support he is now severely vulnerable. I’ve looked after him for 50 years and this is the worst time I have ever experienced. It is going back to Victorian times, people left in incontinence pads for 12 hours.”

What about the children whose future chances may depend on the library at the end of the road? “I’m sorry to say this, but I don’t see how they can justify keeping a library open when there are severely disabled people with no care,” the mother says kindly. “You can’t compare books with lives.”

This is the Cameron government’s legacy, choosing between learning and care. It is not Hobson’s but Osborne’s Choice.

In a warm Wolverhampton council flat, we meet Bernie Phillips, a 65-year-old charity volunteer who tells us about feeding her grandchildren on crackers and hiding from bailiffs after her husband and daughter died and the benefit system failed to kick in.

“They ate first,” she said. “Then me, if there was enough. I’m Irish. We know how to make meals out of nothing but there was just so little. We lived on little meals, cheap food – cheese and crackers, 10p crisps, beans on toast and cereal.”

Orwell spent the night not in these proud but struggling towns but on the hillside above the town of Stourbridge, a five-mile walk into the rolling fields. “Walked 4-5 miles to Clent Youth Hostel,” he wrote in his diary. “Red soil everywhere. Birds courting a little.”

We have been told the hostel is now the Clent Community Social Club. When we visit with local historians from the Orwell Society, Dr David Craik and Neil Smith, club stewardess Dawn Bubb tells us the deeds of the place date back to the 1920s.

That evening, at the bar, we find a resident as old as The Road to Wigan Pier. Bill Haynes, a former steelworker who served in the Veterinary Corps, was born within weeks of the book’s publication on March 8 1936. Clent hasn’t changed one bit in 80 years, he says. “It’s still exactly the same.”

Comfortable night in hostel which I had to myself. One-storey wooden building with huge coke stove which kept it very hot. You pay 1/- for bed, 2d for the stove and put pennies in the gas for cooking. Bread, milk etc on sale at hostel. You have to have your own sleeping bag but get blankets, mattresses and pillows. Tiring evening because the warden’s son, I suppose out of kindness, came across and played ping-pong with me till I could hardly stand.

Orwell in the Clent Hills, diary entry on the Road to Wigan Pier

Orwell had strict rules about pubs, creating his own imaginary local, the Moon Under Water. His ideal pub had to be two minutes from the bus stop, sell draught stout, be quiet enough to talk, have “motherly barmaids”, a garden and glasses with handles.

With the help of its customers, we tick off 10 out of 14 points at the social club – all for £3 a year membership (£5 for couples). Bonus points are awarded for a local speciality, an implausibly sized pork pie.

Then Bill remembers the cottage next to his was a youth hostel when he was growing up. Orwell described it as a “one-storey wooden building with huge coke stove which kept it very hot. You pay 1/- for bed, 2d for the stove and put pennies in the gas for cooking.” Bill laughs. “That must be the one.” Orwell played ping-pong at the hostel with the warden’s son till “I could hardly stand on my feet”.

At the club we meet Kate Gallimore, an NHS surgeon at the local hard-pressed hospital. “She’s from Wigan,” her husband Duncan says, showing her the book.

Kate admits that not many Wiganers love The Road to Wigan Pier. “I think Orwell was just trying to be truthful. But what he found wasn’t very nice at that time – working conditions were really awful.”

In March 1936, the weather turned overnight for Orwell, who says local people “thought me a hero to be walking on such a day”. In 2017 we wake early to find the red soil of the hills blanketed with snow.

From the viewing point at the top you can see five counties on a clear day, so somewhere beyond the white-out must be Orwell’s next stop. It was in Stoke-on-Trent that he began to encounter the conditions leading to the rise of Oswald Mosley, the founding leader of the British Union of Fascists.

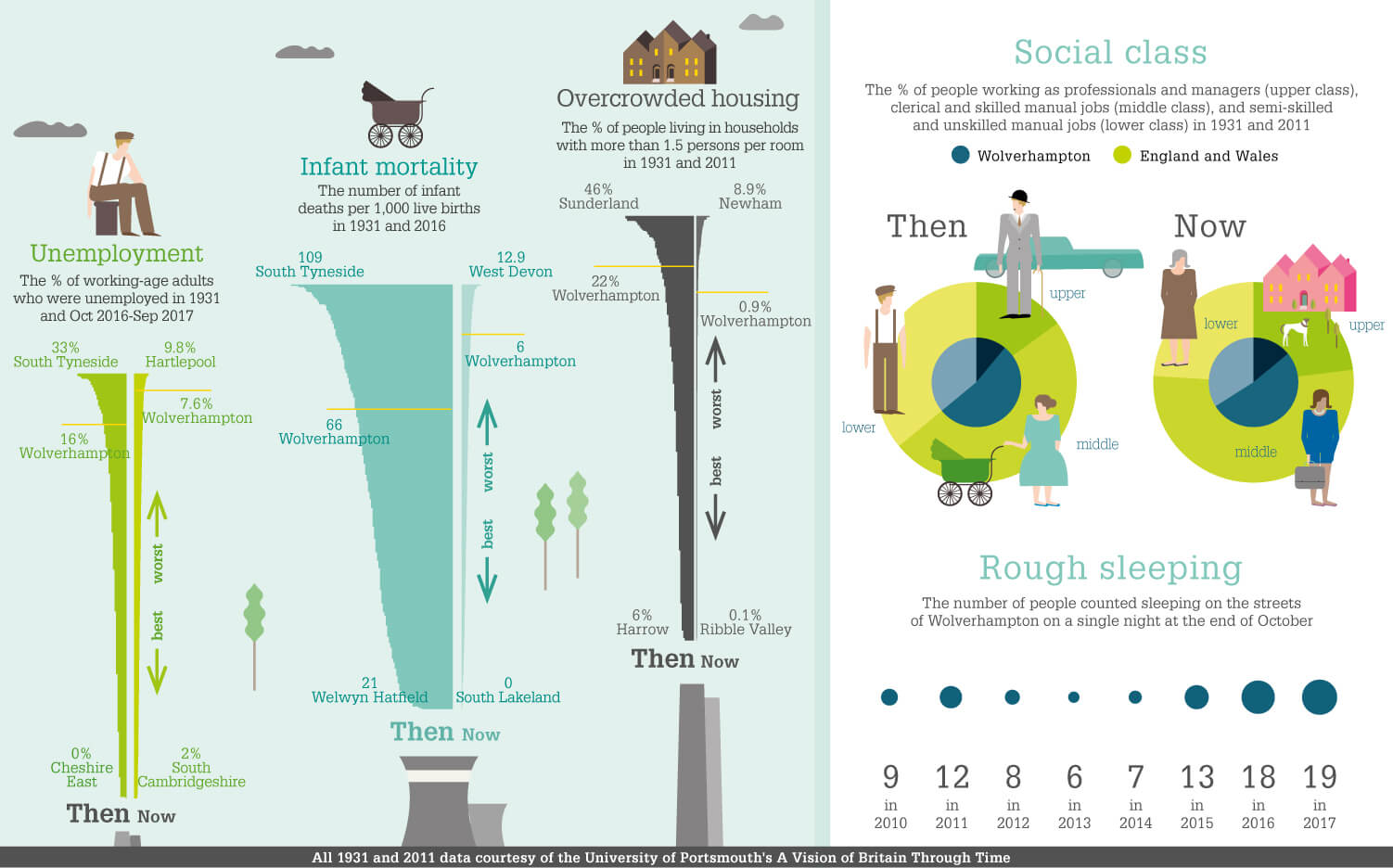

What the numbers say

Your story

If you live in any of the places mentioned in the Wigan Pier Project and have a story to share, please get in touch.

You can contact us via wiganpier2017@mirror.co.uk tweet us at @WiganPier80 or write to Wigan Pier Project, Daily Mirror, One Canada Square, Canary Wharf, London E14 5AP

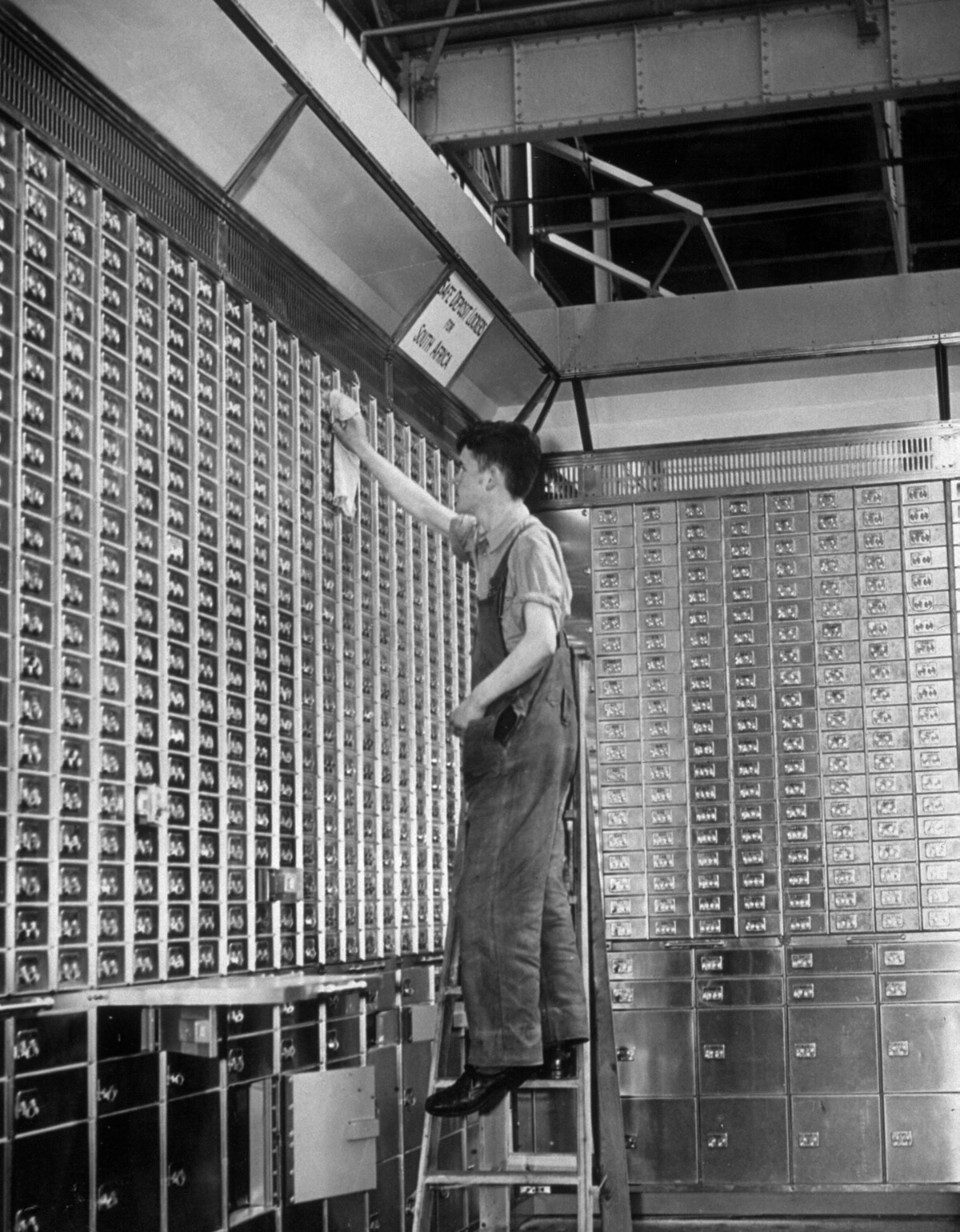

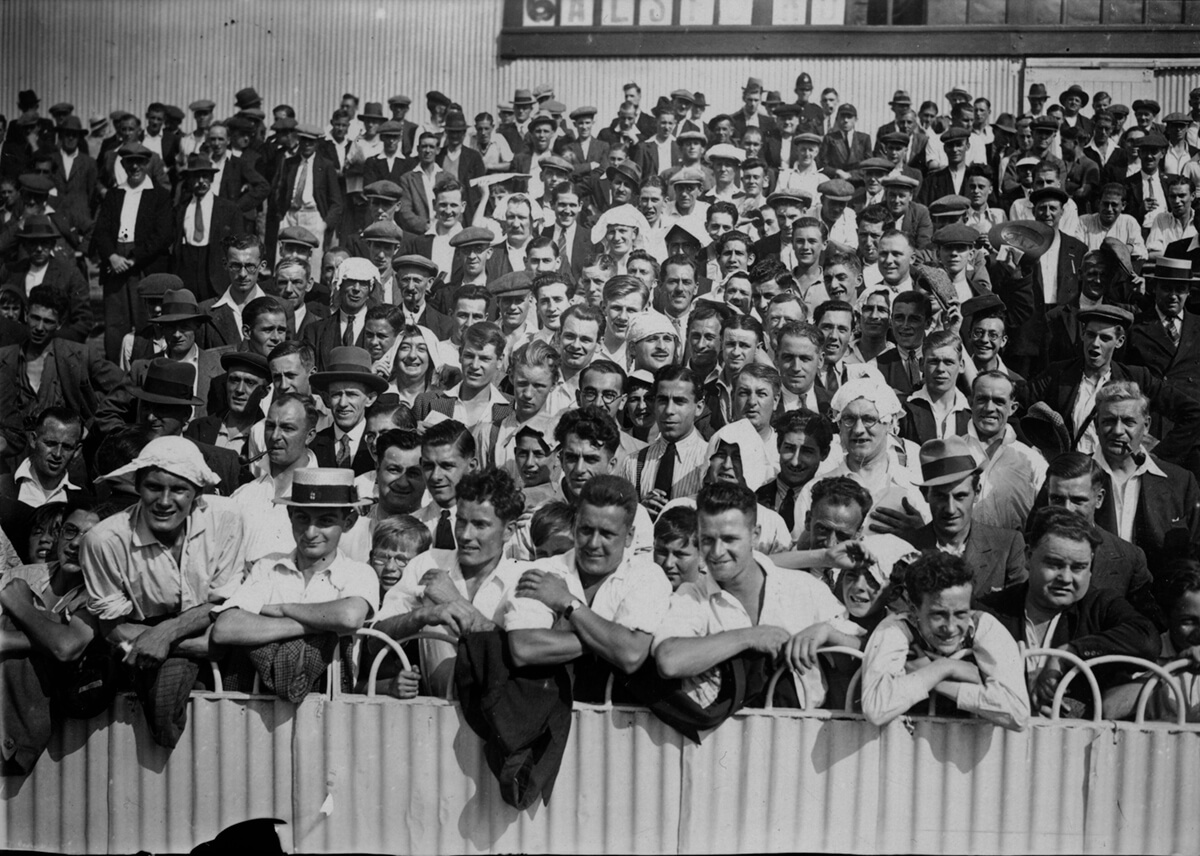

From the archives

Fascinating photographs from the Mirror archives showing what Wolverhampton looked like when Orwell visited

For housing advice

For housing advice

For general advice

For general advice

For foodbank help

For foodbank help

For help in work or out of work

For help in work or out of work