In Macclesfield we find farmers are losing out to footballers

As farmers see their livelihoods vanish, we meet a boxing coach who is turning kids' lives around

Mike Gorton stands on the rented land his family has farmed for four decades, his tractor silent but still kicking out heat beside him.

“We sold the herd on my father’s 86th birthday,” he says quietly, looking out across quiet fields mowed into wide avenues for silage. “It broke his heart. He didn’t speak to me for three weeks. But if we’d carried on we would have been bankrupt.

“Loading the lorry up was horrendous. There were heifers I’d raised since they were calves and watched them have their own calves. Animals you’ve had to pull out at 4am, taking them from the brink of death into life.”

When Mike’s family moved to Cheshire from the Midlands to become tenant farmers in 1976, his neighbours were all farmers. Now they are footballers.

“That’s the Rooneys’ land up there,” Mike points out, sunburned face turned towards Prestbury. “The farmworker’s cottage next door just sold to Manchester City’s third goalkeeper”.

We are in Macclesfield for the Wigan Pier Project, retracing George Orwell’s steps. Cheshire might appear to have been one of the more affluent stops on The Road to Wigan Pier writer’s journey, yet farmers here were also weathering hard times in the depression of the mid-1930s, when this farm lay empty.

When he was forced to sell his herd in 2015, Mike was earning 15p a litre for milk it was costing him 25p a litre to produce. Poignantly, the cows he used to own still graze here, as he looks after them for their new owner. “But the reality is I can no longer call myself a farmer,” he says. “I’ve basically joined the service industry.”

In rural Britain, what city folk call gentrification literally means farmers are being wiped off the soil. Rolling countryside is worth more in an estate agent’s window than for feeding a population intent on ever-cheaper food.

“There used to be 27 working dairy farms in this area,” says Mike, who is on the Dairy Board of the National Farmers’ Union. “Now there are none. There used to be 100,000 dairy farmers in England and Wales. Now there are 9,000. There’s a whole nation of farmers in my position up and down the country.”

Many of Mike’s generation of farmers gave up the land to become “rat mechanics” at the nearby AstraZeneca pharmaceutical plant. “If you’ve got a farming background you were welcomed with open arms because you were used to dealing with animals,” Mike says. The firm has since moved this facility to Cambridge.

Since Brexit, farming’s future is even more uncertain. Farmers who voted enthusiastically for Leave are now finding bank loans are drying up. So potentially is the supply of European labour as we face crashing out of the single market.

While the country throws away £13billion of food waste every year, British farmers have one of the highest suicide rates of any profession, with one farmer a week taking their own life. The cocktail of isolation, money worries, gruelling hours and no holidays is a powerful one. Recent studies suggest a quarter of farmers live below the poverty line.

After Mike spoke out about losing his herd he was moved by messages from the public begging him to keep going. “It did keep me going, to know that people do care,” he says. “The worst thing is thinking that no one gives a toss. If your self-worth disappears, you’re a goner.” I wonder if he ever talked to his cows about his money worries and he nods seriously. “The cows heard a lot about it,” he says. “That’s no joke.”

Mike and his family have found a way to survive but nearby hill-farmers are in far worse shape. While urban families miss meals to feed their children, there have been stories of farmers missing meals to feed their flock. “Sheep farmers are the ones who, without some sort of help, face being wiped out by Brexit,” Mike says.

This rural leg of Orwell’s journey takes in the still blue waters of Rudyard Lake where Orwell spent the night in a freezing youth hostel in February 1936, publishing The Road to Wigan Pier the following year. The writer made a detour to see the lake because it was where his hero Rudyard Kipling’s parents met, naming their son after it.

The hostel building is still there but derelict now, birds flying in through broken windows. Orwell’s diary recalls the bitter cold of the night at the hostel, the flyblown pleasure boats and the clank of broken ice on the water, “the most melancholy sound I ever heard”.

Got out of bed so cold that I could not do up any buttons and had to [go] down and thaw my hands before I could dress. Left about 10.30am. A marvellous morning. Earth frozen hard as iron, not a breath of wind and the sun shining brightly. Not a soul stirring. Rudyard lake (about 1½ miles long) had frozen over during the night. Wild ducks walking about disconsolately on the ice. The sun coming up and the light slanting along the ice the most wonderful red-gold colour I have ever seen. Spent a long time throwing stones over the ice. A jagged stone skimming across ice makes exactly the same sound as a redshank whistling.

Orwell on Rudyard Lake, diary entry on Wigan Pier journey

It is still lonely in bright sunshine. We meet only two walkers, a kayaker and two musicians recording a video for an Orwellian-themed song about the self-obsession of social media.

Following Orwell’s route to Macclesfield, we stop in the Prince of Wales pub in the town centre. At 47, landlord John Hitchener is just old enough to have worked in the silk mills that once brought the town’s prosperity.

“I wish we could have held on to our heritage as a town,” he says. “There used to be silk, cotton. A lot of the men in here will be old enough to remember the knocker-uppers who ran round getting people up for work. There were houses for the workers. Now young people can’t get on the ladder and the working opportunities aren’t there.”

A short walk from the Prince of Wales, in a subterranean gym below a bathroom shop, Macclesfield Boys’ Boxing Club is in full flow. In Orwell’s day Macclesfield had a proud boxing pedigree and for the last 14 years the club has set about restoring the town’s pride. Boys and girls box for £1 a session.

“We’ve had some great wins,” says head coach Kevin Bradbury, 49. “But it’s not about that. It’s about turning kids’ lives around. You can’t save them all. But you try.”

Co-founder Gary White, 51, says all the kids look forward to the annual trip to Blackpool. “Last summer one of the boys saw the sea and said ‘What’s that?’ He ran right the way down the beach into the water. You could see him licking his lips. He’d never tasted saltwater before.”

Kevin nods. “We had a girl doing every drug going, fighting every week, in trouble with the police,” he says. “Three times national champion now. She’s boxing in the Army. She’s in the GB talent programme. Another one who was expelled, excluded – we saw straight away he was a right brainbox. He’s at Oxford University now.”

On nearby Moss Rose estate, many of the kids come from families where the maths of daily life doesn’t add up.

“People here are stressed and struggling,” says Rev Rob Wardle, 59, from the Cre-8 project run by St Barnabas Church. “Parents are working longer hours for less, living with zero-hours contracts and austerity and that impacts on their kids. There’s a lot of in-work poverty here, a lot of latchkey kids.

“There are modern-day Fagins around. They use young lads to help with criminal activity. It’s a kind of grooming. Young people are vulnerable but don’t always realise it.”

Everyone we meet worries about Macclesfield’s next generation. “When I finish here, it’ll never be a farm again,” Mike says. “My kids don’t want to be farmers – they’ve seen what we’ve gone through. This will be a house with fields, like most of our neighbours.”

His parting words hang in the air with the pollen haze floating above his neatly mown fields.

“We need to really think what we want from our countryside,” he says. “Lots of big houses or food production? If the hill-farmers go to the wall after Brexit, we’re really facing the end of the countryside as we know it.”

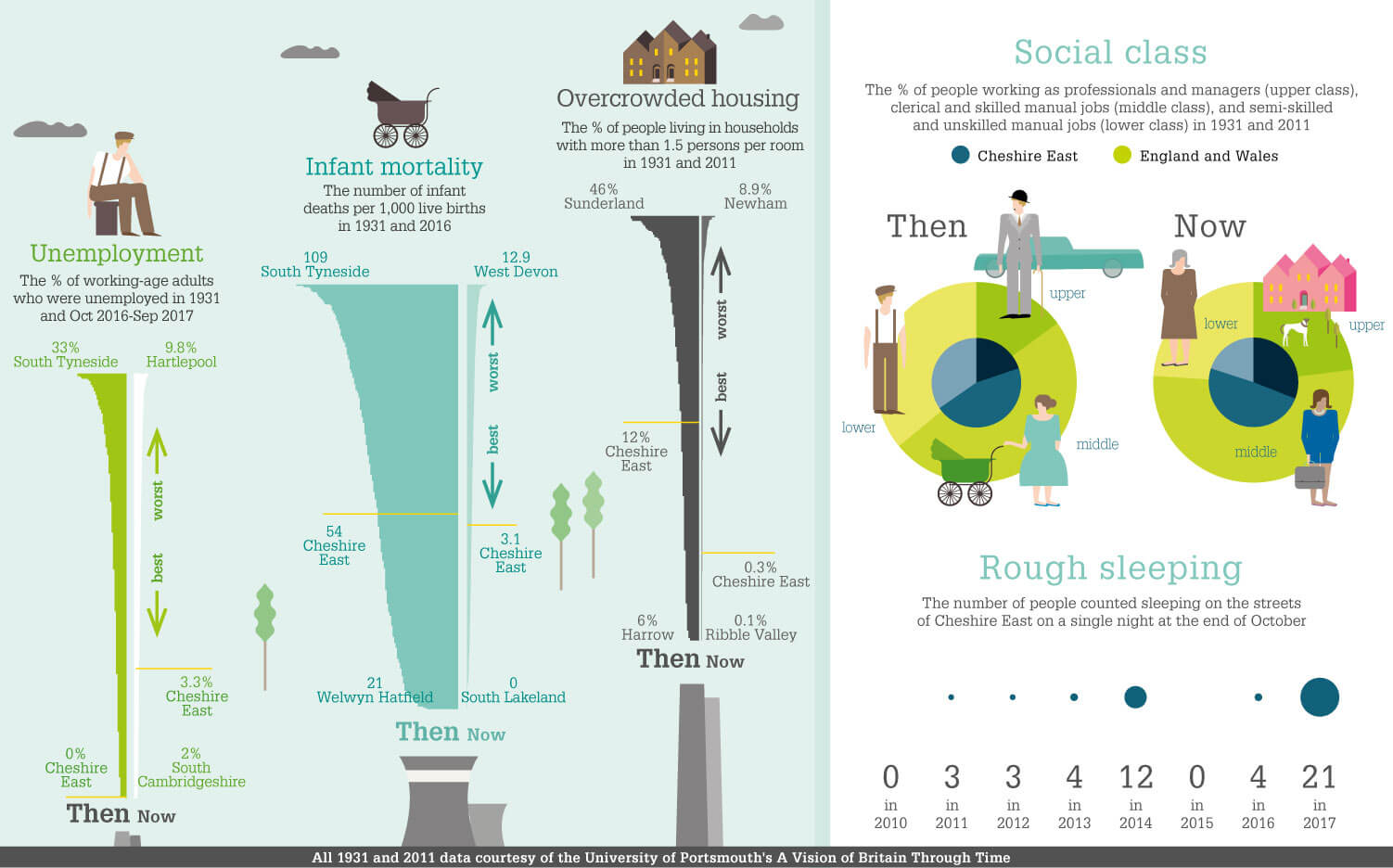

What the numbers say

Your story

If you live in any of the places mentioned in the Wigan Pier Project and have a story to share, please get in touch.

You can contact us via wiganpier2017@mirror.co.uk tweet us at @WiganPier80 or write to Wigan Pier Project, Daily Mirror, One Canada Square, Canary Wharf, London E14 5AP

From the archives

Fascinating photographs from the Mirror archives showing what Macclesfield looked like when Orwell visited

For housing advice

For housing advice

For general advice

For general advice

For foodbank help

For foodbank help

For help in work or out of work

For help in work or out of work