When Orwell reached Liverpool, his guide was George Garrett, an almost unknown working-class writer

He may not be as famous as Orwell, but the other George changed the world with his words and social action, by Ros Wynne-Jones and Claire Donnelly

The Road to Wigan Pier, which the Mirror has been retracing for the past 15 months, turns out to be a tale of two Georges – George Orwell, the writer in whose steps we are following, and George Garrett, the almost unknown working-class writer, activist and merchant seaman.

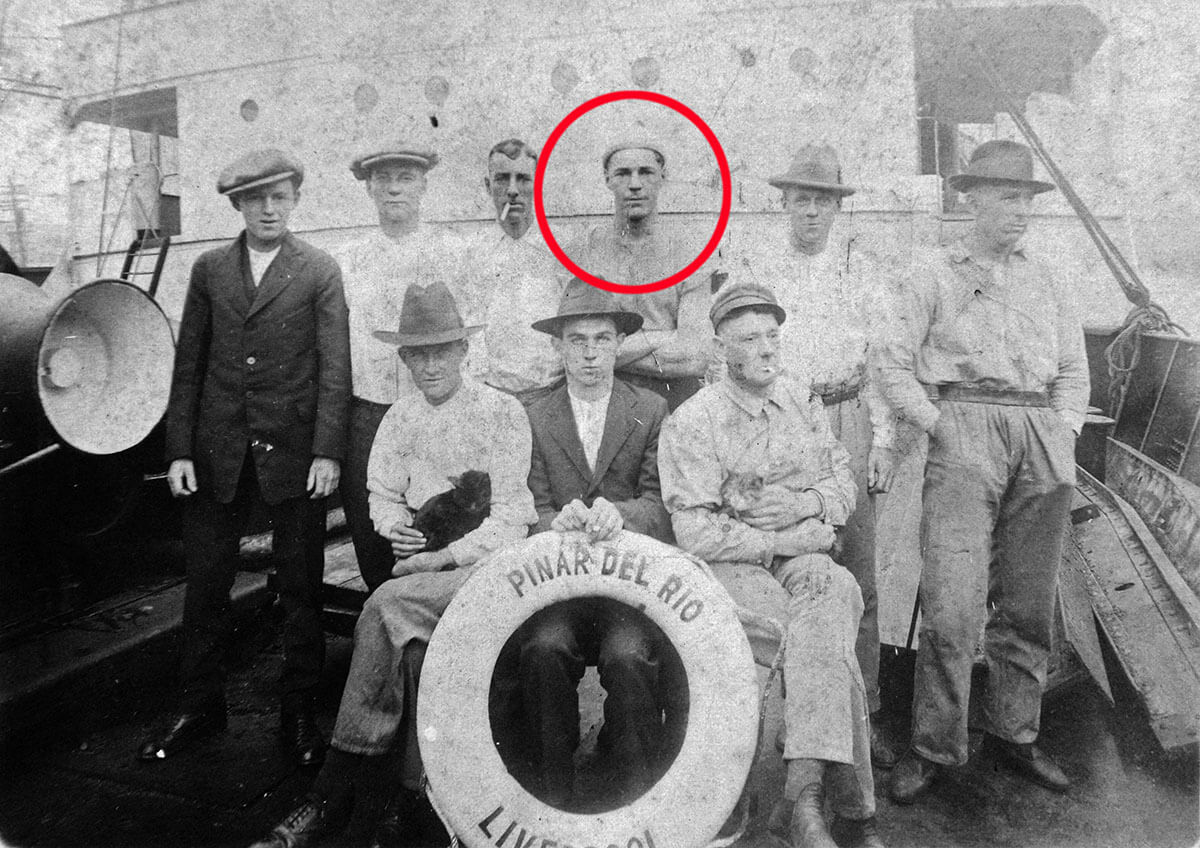

“I was very greatly impressed by Garrett,” Orwell writes in his 1936 diary. “He went to sea as a lad and was at sea about 10 years, then worked as a docker. During the war he was torpedoed on a ship that sank in seven minutes. He also worked in an illicit brewery in Chicago during Prohibition, saw various hold-ups and saw Battling Siki [briefly world light heavyweight boxing champion] immediately after he had been shot...”

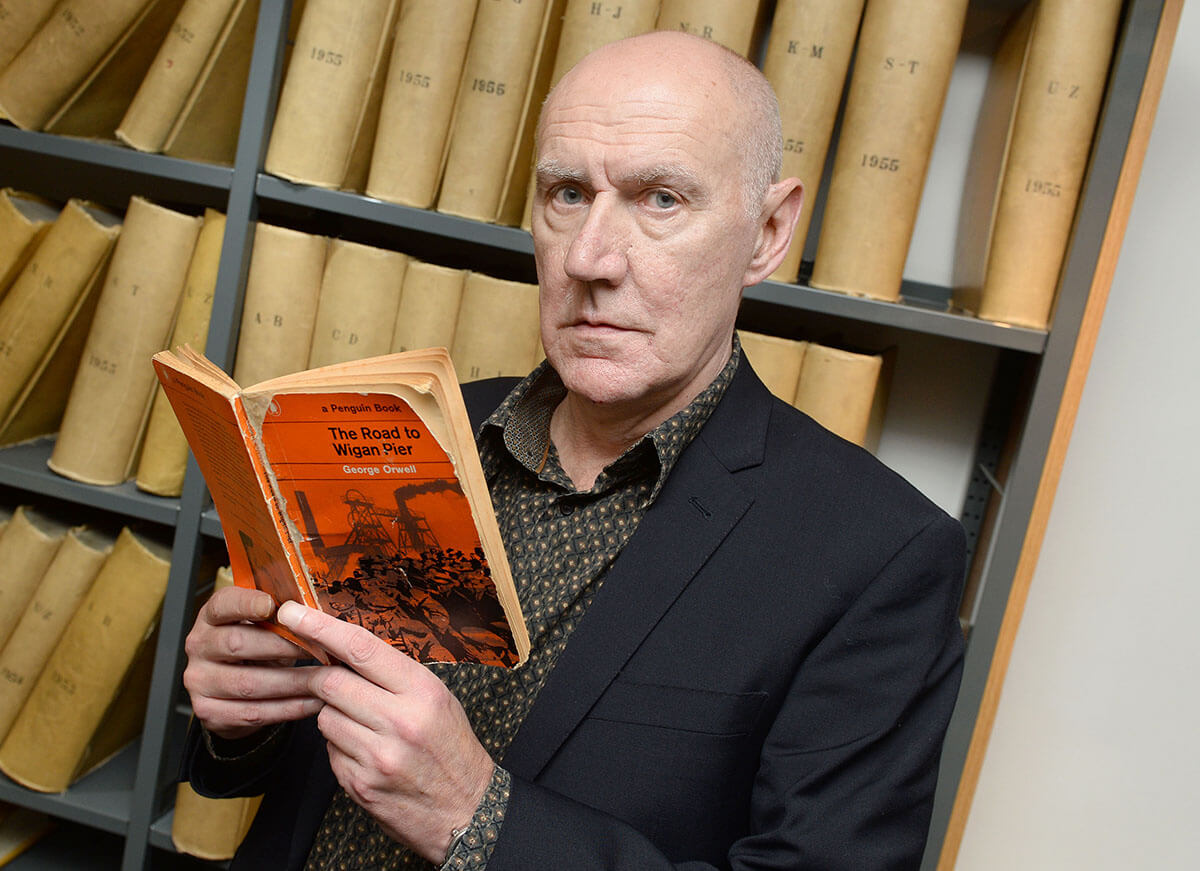

When Orwell reached Liverpool on his journey to Wigan Pier, Garrett, a stoker from Sailortown, Belfast, was his guide. Eight decades on, we are greeted by Sean Garrett, his grandson. Sean smiles when we talk about Orwell, who his grandad accused of writing “one long sneer” against the working classes. “I find myself defending Road to Wigan Pier,” he says. “I can see Orwell had the right intentions.”

Sean, 58, works in a homeless shelter, so sees modern-day poverty in Liverpool close up. “After the poverty he lived in, men like my grandad helped build the welfare state,” he says. “Seeing all that thrown away now by Tory austerity, he’d be heartbroken.”

While Eton-educated Orwell could escape any time from his hard road, for Garrett writing was a luxury he had to fight for against the demands of work at sea or on the docks and the needs of his wife and seven children. When they met, Garrett was unemployed or ‘on the parish’. They were physical opposites: Orwell long and thin with a smoker’s cough, Garrett with a stoker’s strength. “I remember him as Popeye the sailor-man,” his grandson says. “Huge biceps. A big strapping fella, very physical in a lovely way.”

He was unusually progressive for an 1896-born stoker, a feminist and an anti-racist

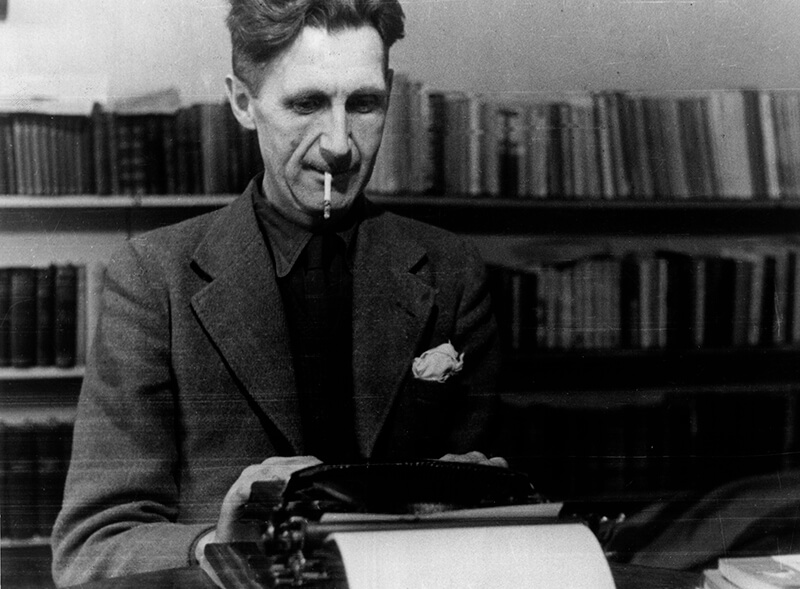

The Georges did share other things – writing talent, stubborn honesty and a thirst for travel, outdoor life and experience. They both wrote under pseudonyms – Orwell’s real name was Eric Arthur Blair and Garrett often wrote as Matt Low. Both wrote books documenting the struggle of the working classes in the 1930s.

But Orwell’s, a middle-class writer’s tour of poverty in the industrial North, became a literary classic. Garrett’s book, Ten Years on the Parish, which described his own experiences, went unfinished and languished in near obscurity until now.

Four years ago, Sean’s brother Michael turned over a suitcase of Garrett’s merchant navy papers and unpublished writing to the Writing on the Wall project, based in Toxteth Library. Through the George Garrett Archive project, a group of volunteers have rebuilt a man and reputation from scraps of paper. Now published for the first time, Ten Years on the Parish is so extraordinary it reads like a novel – starting from the moment Garrett stows away aged 17 on a tramp steamer bound for Argentina.

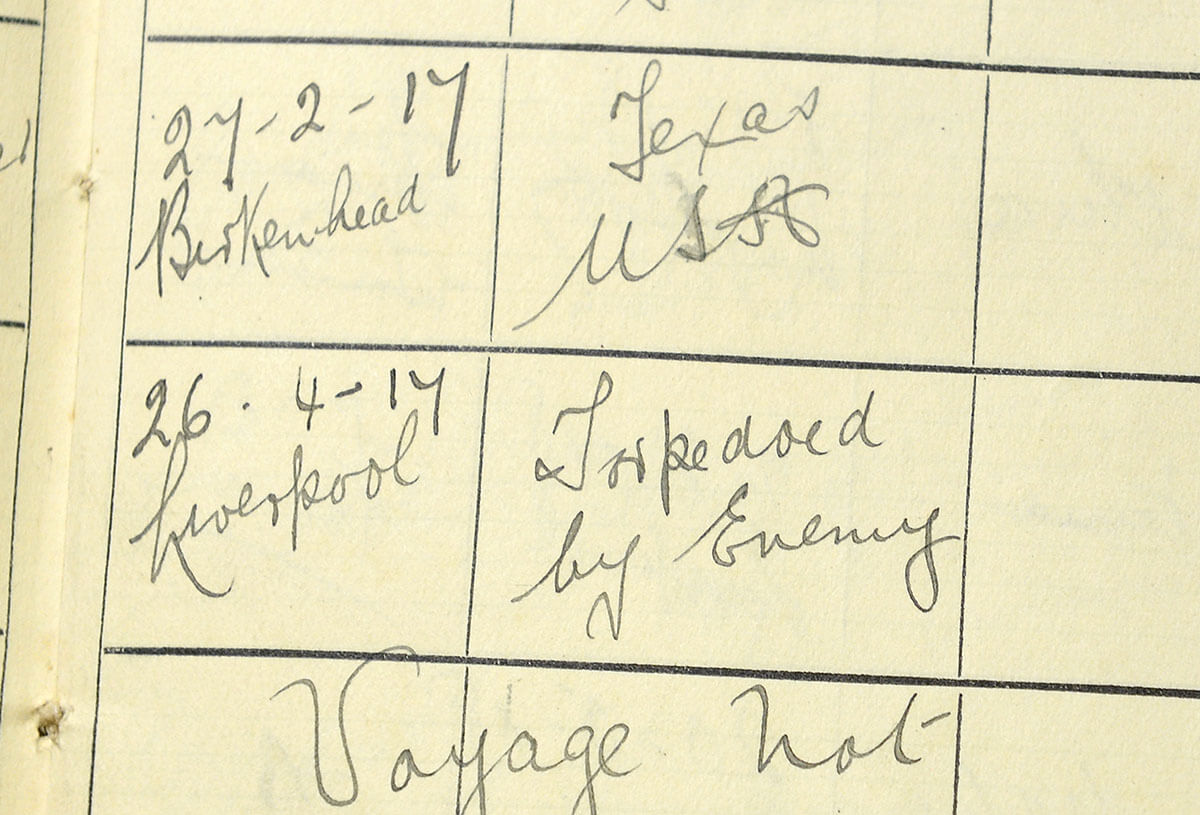

“That’s his log book from the merchant navy,” Sean says, pulling out a booklet from the archive now housed by Liverpool Central Library. Seaman 805334’s adventures from saloon boy to stoker are recorded in neat fountain pen. “Captured 17th March 1916”. “Torpedoed by the enemy”.

Garrett was sunk twice during the war and once interned but escaped. He later lived in New York as an illegal immigrant, sending home far higher wages than he would have earned in Liverpool and joining the Industrial Workers of the World labour union, known as the Wobblies.

When Garrett wasn’t at sea he was leading the fight for workers’ rights in Liverpool and helped found the Unity Theatre. He was unusually progressive for an 1896-born stoker, a feminist and anti-racist who, as the son of a staunch Catholic and a Belfast Orangeman, had no time for sectarianism.

“He took part in the Walker Art Gallery Riot and was battered by the police,” Sean says, showing us the £50 fine from the city of Liverpool. “He led the National Hunger March on London as part of the Liverpool contingent in 1922.”

Garrett’s most famous speech at the docks, recorded for posterity by an undercover policeman after race riots in 1919, could have come straight from today. “Fellow workers, it is all very well criticising the alien… and telling you he is the cause of your unemployment. It is not so. The present rotten system is the cause…”

Garrett was desperately disappointed when he read Orwell’s book. “A book like that can do a lot of damage,” he wrote to his publisher John Lehman. Ten Years on the Parish lacks Wigan Pier’s forensic detail but is vividly readable. It tells of stowing away on the voyage to Buenos Aires, Liverpool children running from the “night man” who checked whether families were “‘improperly” sharing beds, and the busybody parish officials lifting pan lids to see whether mothers were squandering money. The misery of food vouchers, poor relief and unemployed men being forced to break stones contrasts dramatically with the camaraderie of the Hunger March on London.

I was very greatly impressed by Garrett. Had I known before it is he who writes under the pseudonym of Matt Lowe, I would have taken steps to meet him earlier. He is a biggish, hefty chap of about 36, Liverpool-Irish, brought up a Catholic but now a Communist. He says he has had about 9 months’ work in (I think) about the last 6 years. He went to sea as a lad and was at sea about 10 years, then worked as a docker. During the war he was torpedoed on a ship that sank in seven minutes but they had expected to be torpedoed and had got their boats ready and were all saved except the wireless operator, who refused to leave his post until he had got an answer. He also worked in an illicit brewery in Chicago during Prohibition, saw various hold-ups, saw Battling Siki immediately after he had been shot in a street brawl, etc, etc.

Orwell’s diary entry on meeting George Garrett in Liverpool, The Road to Wigan Pier

As the Liverpool writer Frank Cottrell-Boyce says: “We read the Road to Wigan Pier to see how poverty looked to a sympathetic, intelligent, compassionate outsider. We read Garrett to find out how poverty felt. From the inside... Garrett’s desperation for money – and time – quivers through every sentence”.

Mike Morris, co-director of Writing On The Wall, says: “His tenement was desperately overcrowded. But when Garrett went to the library people would collar him for help with writing and advocacy. He was like a one-man Citizens’ Advice Bureau. He always had that struggle – his principles and loyalty to his class versus his creativity.”

Historian Alan O’Toole says it is remarkable “not that George wrote so little” but “that he wrote so much”.

Garrett had a breakdown just as publishers came knocking for a sea novel. “He couldn’t have afforded to go to London to meet those publishers anyway,” Sean says. Instead, he left a legacy of short stories, plays and the more socially secure world built by his generation.

Sean’s glad his grandad can’t see the country 80 years on.

“He’d be appalled and angry at the erosion of workers’ rights, racism in the wake of the Brexit vote, foodbanks, the depiction of the working class and the relentless pushing back of the welfare state,” he says. “After everything his generation achieved, the upper classes pushed right back. Now people are back on the street, back in new slums.”

Nevertheless, in spite of the frightful extent of unemployment, it is a fact that poverty – extreme poverty – is less in evidence in the industrial North than it is in London. Everything is poorer and shabbier, there are fewer motor cars and fewer well-dressed people; but also there are fewer people who are obviously destitute. Even in a town the size of Liverpool or Manchester you are struck by the fewness of the beggars… in the industrial towns the old communal way of life has not yet broken up, tradition is still strong and almost everyone has a family – potentially, therefore, a home. In a town of 50,000 or 100,000 inhabitants there is no unaccounted-for population; nobody sleeping in the streets, for instance.

Orwell on Liverpool, The Road to Wigan Pier

Sean says the people at the homeless shelter he works at are there “just because the rent has gone up or because of welfare changes”.

He has no doubt what George would be doing about it. “He wouldn’t be taking it standing still,” he says. “He would be using his skills as a writer, organiser, advocate and activist to push aggressively back. And I feel sure he would have rejoiced in the new-found engagement and enthusiasm of young people with progressive ideas and politics.”

Orwell died in 1950 of tuberculosis after finishing his masterpiece 1984 and fighting in the Spanish Civil War. Garrett was last seen in public giving a speech during the 1966 seamen’s strike, despite having throat cancer. Then he gave his bus fare to the collection for the striking men, walked home and died.

www.georgegarrettarchive.co.uk

Ten Years on the Parish is published by Liverpool University Press

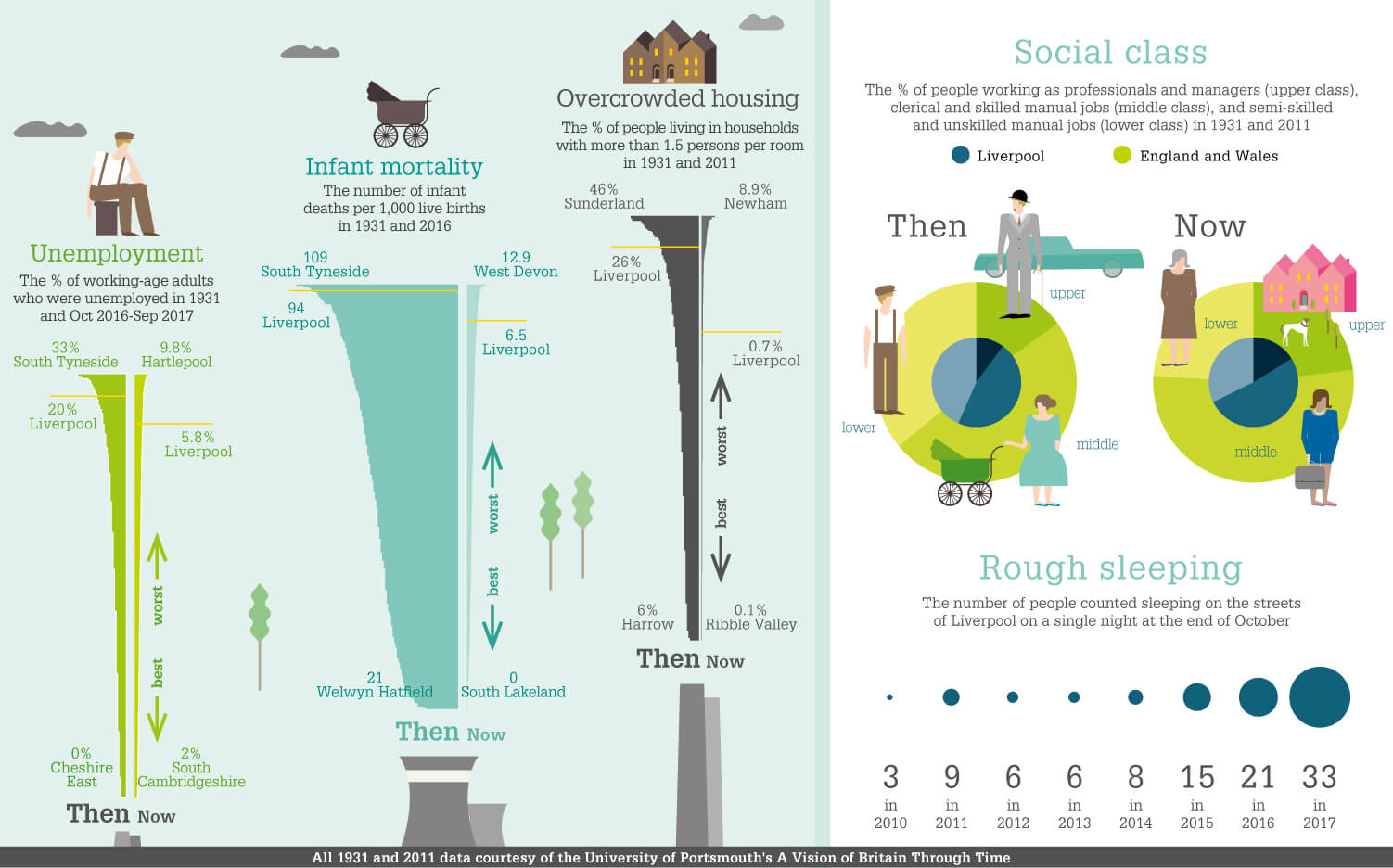

What the numbers say

Your story

If you live in any of the places mentioned in the Wigan Pier Project and have a story to share, please get in touch.

You can contact us via wiganpier2017@mirror.co.uk tweet us at @WiganPier80 or write to Wigan Pier Project, Daily Mirror, One Canada Square, Canary Wharf, London E14 5AP

From the archives

Fascinating photographs from the Mirror archives showing what Liverpool looked like when Orwell visited

For housing advice

For housing advice

For general advice

For general advice

For foodbank help

For foodbank help

For help in work or out of work

For help in work or out of work