The Wigan Pier Project

The Wigan Pier Project was devised by Ros Wynne-Jones but none of it would have been possible without the inspiration of George Orwell. Here, Orwell's adopted son reveals the caring side of the literary legend and we say thank you to everyone who made the project possible

George Orwell's adopted son reveals how his dad cared for him while he wrote classic 1984

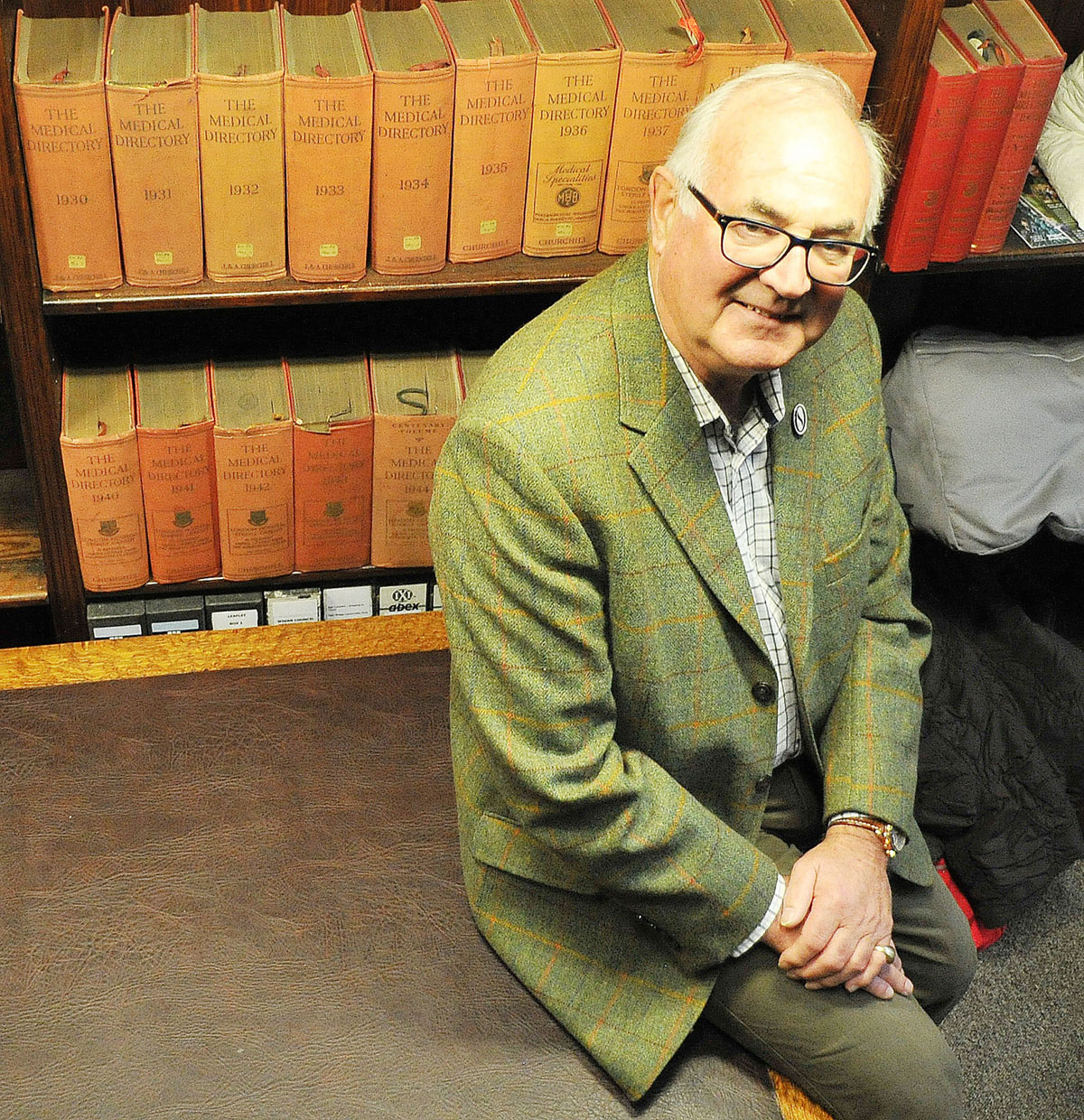

Eight decades after Richard's father researched Wigan Pier in the attic room of the town's old library, Richard has returned with the Orwell Society to retrace his steps

Richard Blair smiles remembering his father, who died when he was just six. 'I remember him changing my nappy and feeding me after my mother died,' he says. 'And I remember the clack of his typewriter.

'His voice was soft and husky and he was tall and gaunt at that point, as he was already suffering from tuberculosis.'

Richard's father was George Orwell, author of 1984, Animal Farm and The Road to Wigan Pier.

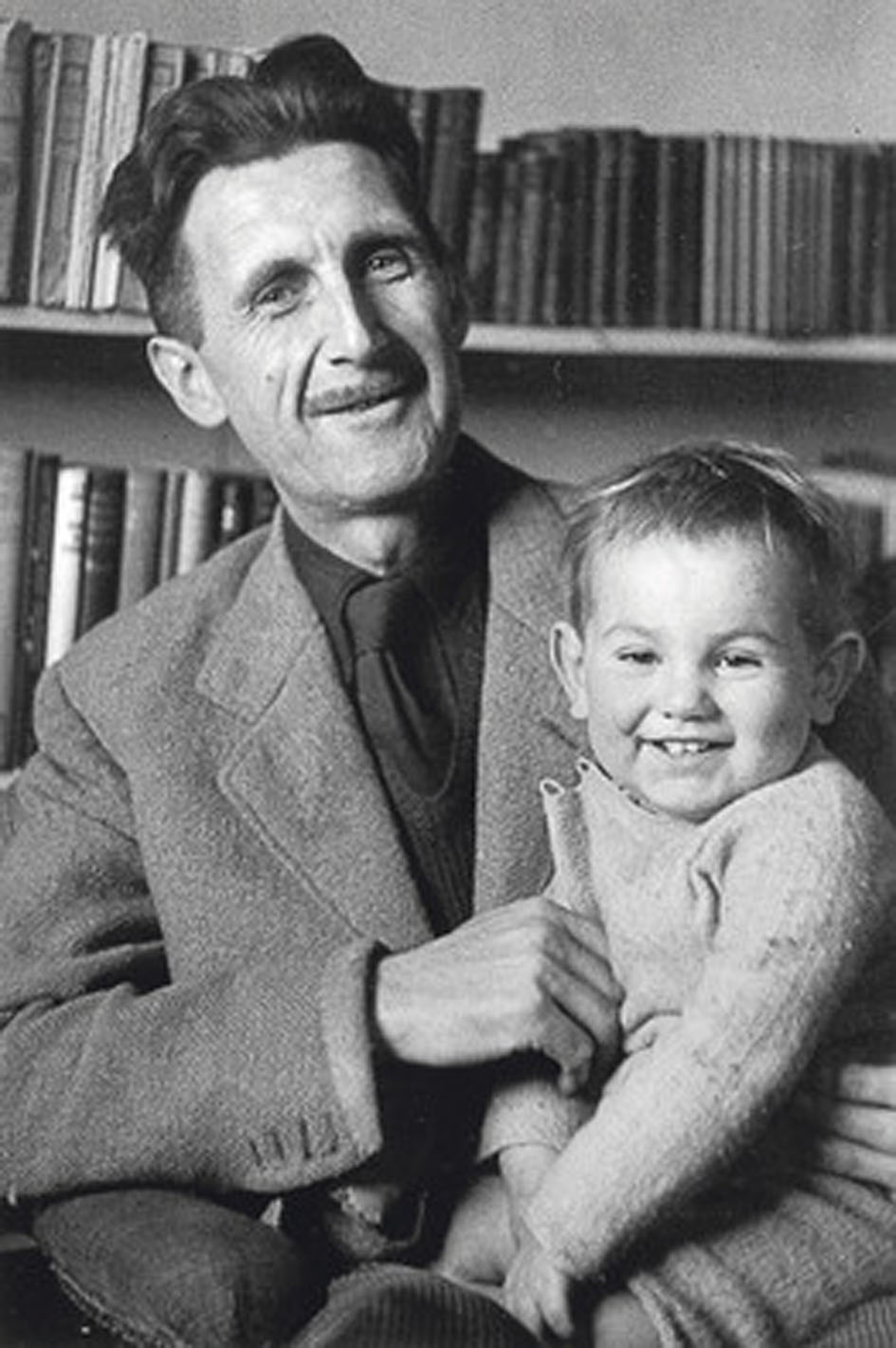

Very little survives of him as a family man, except Richard's memories and a few black and white photographs of the writer squinting into his cigarette smoke as he plays with his son.

Now a retired engineer, Richard, 72, offers a tender portrait of a warm, loving man.

'He was a wonderful father,' he says.'He was really hands on in a way that was really unusual for that era.'

It is 80 years since his father published the groundbreaking Road to Wigan Pier and, throughout 2017, the Daily Mirror is running our own Wigan Pier Project, retracing Orwell's steps through former industrial heartlands of the country.

Eight decades after his father researched Wigan Pier in the attic room of the town's old library, Richard has returned with the Orwell Society to the town made infamous by the story. His father's neat signature is in the library book in front of him: 'E.A. Blair, 72 Warrington Lane – 13th February 1936.'

'My father loved the people of Wigan,' Richard says. 'People sometimes misunderstand that. The conditions were appalling but that was the same all over the industrial North. Wigan became a metaphor for social problems, but that wasn't his intention.'

Eric Arthur Blair, who took the name George Orwell to avoid embarrassing his family by sleeping rough during research, died in January 1950 at just 46. He had adopted Richard six years earlier. 'My father really wanted a child, but he believed he wasn't able to have one,' he says.

Orwell's first wife Eileen's sister-in-law, Dr Gwen O'Shaughnessy, knew of a woman who was pregnant; her husband was away fighting in the Second World War. Orwell and Eileen adopted Richard at three weeks old. His new father burned the birth parents' names from the certificate with a cigarette.

Nine months later, Eileen died while being given anaesthetic for a hysterectomy.

It was 1945, and Orwell was on his way to Germany to report on the war for The Observer. He was in Paris when he got the news. 'He came straight home to organise the funeral,' Richard says. 'Friends suggested that my father should un-adopt me. He said, I've got my son now, I'm not going to give him over.'

Orwell and Richard lived on remote Hebridean island Jura for much of 1945 to 1950, at Barnhill, a farmhouse only reached by boat or several hours' walk. It had no electricity or telephone.

Orwell spent the days feverishly writing his masterwork, 1984, as his tuberculosis worsened. Richard was often left to look after himself, although he initially had a nanny, and later Orwell's younger sister Avril cared for him.

'He would write all day and you would hear him tap, tap, tapping on the typewriter,' Richard says.

Orwell tried to balance his fear of passing on TB to his son and his desperate desire not to be a distant father. Writer and son went on long fishing trips.

When Richard's cousins Henry, Jane and Lucy came to stay in August 1947, Orwell took the children on a camping trip in the dinghy. On the way back, he misjudged the tide and the boat was battered by the notorious swell at the Gulf of Corryvreckan.

Orwell was steering with the outboard when it was pulled off by the tide. Henry, just returned from national service, took the oars and managed to row the boat to a rocky island. But as he dragged the boat up on to the shore, it slipped backwards on the barnacles and capsized.

'My father and I both went under the tipped-over boat,' Richard says. 'Either of us could have been knocked out. But my father managed to get us to shore.' They were rescued by a lobster boat.

A decade earlier, Orwell had been shot in the throat while fighting in the Spanish Civil War. After nearly drowning, his health rapidly deteriorated. 'He smoked constantly,' Richard recalls. 'Black shag roll-ups. He'd use old newspapers if he didn't have cigarette papers.'

Orwell treated his infant son more like an adult. 'One day after lunch, I gathered lots of cigarette ends into his pipe under the table and I asked him for a light.

'A hand came down and he handed me his lighter. You can imagine what happened. Lunch reappeared.'

Another time, Richard was balanced dangerously on a chair watching his dad make a wooden toy when he fell. He still bears the scar on his temple. 'There's a groove in the bone.'

He last saw his father in the sanitorium in Cranham, Glos. Richard stayed nearby at an anarchist colony.

One treasured memory is from the last day they shared on Jura. 'It was his last journey back from Jura, the car had broken down as usual,' he says. 'The others walked back to Barnhill to get the jack. I was left with my father in the car, eating boiled sweets. He told me stories and made up poetry. I think he knew he might not be coming back again.'

Orwell died a few months later, after marrying writer Sonia Brownell on his deathbed at University College Hospital, London. Richard was in Jura with Avril, and heard of his death on the 8pm news. 'Avril became my legal guardian,' he says.

For the last few months, we have been shadowing the writer's elusive ghost. Here, at last, is one of the few people who knew him intimately.

The town is commemorating the 80th anniversary of The Road to Wigan Pier, the legacy of which still divides local opinion. Inside the museum, Orwell's boy remembers the deep love of a father for his only son.

The team

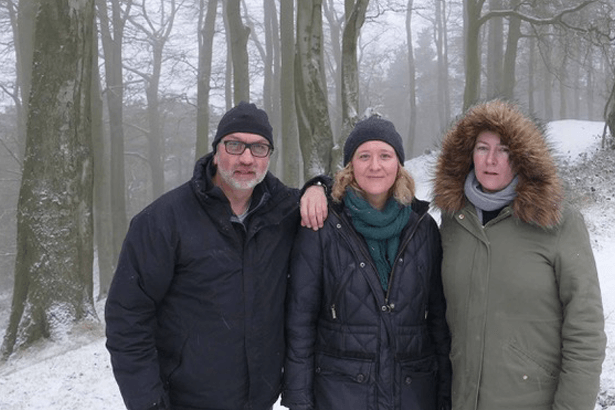

ROS WYNNE-JONES

Ros devised the Wigan Pier Project after visiting Wigan during the 2015 general election and finding pockets of the town returned to the 1930s by modern-day austerity measures, changes in working practices and the sell-off of social housing.

As well as going on to retrace all of the rest of Orwell’s journey – through the Midlands and the north of the country – she also travels the UK for the ‘Real Britain’ column at the Daily Mirror.

CLAIRE DONNELLY

Claire is the WPP’s Communities Editor and is responsible for gathering and co-curating the first-person stories on the site – fulfilling a key aim of the project to allow people to tell their own stories in their own voice and with their consent.

Hailing from Salford, and now living on the Yorkshire/Lancashire borders, ex-Mirror staffer Claire has been instrumental in bringing the project to life.

ANDY STENNING

Almost all of the pictures on this site are taken by award-winning Daily Mirror photographer Andy Stenning, who is based in Manchester.

His photographs show people and their communities as they really are and with the respect they deserve.

Julian Hamilton and Roland Leon also did sterling work on the Liverpool and Midlands legs of the project.

ADAM WALKER

This multimedia site has been designed and built by Adam Walker, the award-winning Multimedia and Interactive Designer for Reach plc Innovations, based in Cardiff.

NORTHERN HEART FILMS

The short films on this site have been created in partnership with the Northern Heart films, documentary-makers based in Darwen, about 20 miles from Wigan. Natasha Hawthornthwaite and Scott Bradley brought unique local insight as well as film-making talent to our project.

ARCHIVE

The beautiful archive pictures on this site from Orwell’s time, belong to Mirrorpix, Trinity Mirror’s photo library. With special thanks to Ivor Game and Fergus McKenna.

ORWELL ESTATE

Use of the text from Road to Wigan Pier and images of Orwell himself are the generous gift of the estate of the late Sonia Brownell Orwell.

THANK YOU

This project would not have been possible without the kind help of the following people – Jean Seaton and the rest of the Orwell Foundation, Bill Hamilton and the Orwell estate, Mirror online especially Ann Gripper and Alison Gow, the Daily Mirror especially Alison Phillips, Peter Willis, Lloyd Embley and Aidan McGurran, Trinity Mirror data unit especially David Ottewell and Annie Gouk, George Orwell’s son Richard Blair, Alex Kann at Together TV, Harry Leslie Smith, Julie Hesmondhalgh, Labour MPs Lisa Nandy, Jess Phillips, Lucy Powell, Rachel Reeves and Lou Haigh whose modern-day constituencies occur along Orwell’s route, Will Somerville, Pauline Doyle at Unite the Union for help in work or out of work, Louise Fazackerley, Fred Hughes, Jack Hood, Stan Shaw, Jean Searle, Anthony Hammond, Alan Gregory, Wayne Atkinson, Barbara Nettleton, Jan Fulster, Rita Culshaw, Des Lynch, Zilla Smith, Cheryl and Julian Porter, Stephen Armstrong, Melanie Powell, Wendy Richards, Bernie Phillips, Mike Gorton, Tom Walsh, Bob Williams-Findlay, Sean Garrett, Mike Morris, Charlotte Hughes, Sandra Faba, Samantha Green, Peter Murray and his students at Manchester Met University, and Matt Flinders and The Sir Bernard Crick Centre at Sheffield University.

ORGANISATIONS

Here are just some of organisations who have supported us along the way: Sunshine House in Wigan, Unite the Union and particularly Unite Community, Trussell Trust, The Wood Street Mission, Manchester, Cornerstone Day Centre, Citizens UK, Rose Vouchers for Fruit and Veg, Khalsa Aid, The Leeds Poverty Truth Commission, The Salford Poverty Truth Commission, UNISON, The Brick Project, Wigan, Christians Against Poverty, Shelter, The People’s History Museum, Writing on the Wall, Liverpool, The Link project, Sheffield, The Basement, Liverpool, The Crypt homeless project in Leeds, Wigan Library, Wigan Mining Museum, SIFA fireside homeless project in Birmingham, RECLAIM, Manchester, Refugee Action, Sheffield City of Sanctuary, The British Association of Social Workers, Kelham Island Museum, Age Concern, the YMCA, The Potteries Museum, Penkridge Market, Spurgeons Young Carers, The Clent Club, Walsall Against Cuts.

Icon and travelling companion

And, of course, more than thanks are due to ERIC BLAIR himself, who during this past two years has become less of an icon and more of a travelling companion.

For housing advice

For housing advice

For general advice

For general advice

For foodbank help

For foodbank help

For help in work or out of work

For help in work or out of work