Birmingham boasts futuristic buildings - but is worse off than in the 1930s

On the first leg of our re-creation of Orwell's journey we visit the city in England worst affected by local authority cuts

Inside a loading bay in the shadow of central Birmingham’s shiny new station, a shapeless figure wrapped in a filthy duvet shifts in his sleep. This same patch of cold concrete, behind two overflowing industrial bins, is where a homeless man, Chiriac Ionut, died just before Christmas in sub-zero temperatures.

Yet within days, someone has dragged a piece of worn cardboard over the memory. “If you find a place you have to take it,” a homeless man tells me. He shrugs. “Beggars can’t be choosers.”

I found the duvet-wrapped ghost when I set out to retrace the steps taken by writer George Orwell as he travelled The Road to Wigan Pier. On January 30 1936, Orwell set out from London to Birmingham via Coventry on the first leg of a journey that awoke the country to the poverty, slum housing, dangerous work and hunger faced by families in the industrial North between the wars.

“The train bore me away, through the monstrous scenery of slag-heaps… foul canals, paths of cindery mud criss-crossed by the prints of clogs,” he wrote. He recorded the “labyrinthine slums and dark back kitchens with sickly, ageing people creeping round and round them like black beetles” and hailed the courage of miners and mill girls. He never found Wigan Pier, which “alas! … had been demolished and even the spot where it used to stand is no longer certain”.

Today, more than 80 years after the book’s publication, with poverty once more on the rise in the UK, the Mirror launches The Wigan Pier Project – dedicated to bringing you the voices of ordinary people struggling to make ends meet all along Orwell’s route.

Throughout the anniversary year on our dedicated website we will bring you stories from the places he stayed in and wrote about – Barnsley, Birmingham, Stoke-on-Trent, Manchester, Liverpool, Wigan, Sheffield, Leeds and the towns and countryside between.

With your help we will chronicle the new rising levels of working and unemployed poverty, the housing crisis, cuts to public services, insecure work and hunger. And with the help of the University of Portsmouth, we will examine data which records poverty in the 1930s and compare it with today.

Poverty is not the same now as in the 1930s, before the advances of the post-war welfare state and when England’s industrial North began to crumble in the wake of the Great Depression. But, as the Tory Northern Powerhouse stands derided as a Poorhouse, there are deep parallels. The depression, banking crisis, growing poverty, the blaming of immigrants and the rise of populism and right-wing ideas would all have been familiar to 33-year-old Eric Arthur Blair as he set out under his pen-name, George Orwell.

By the time the 264-page book was published by Victor Gollancz for members of the Left Book Club, the author was playing his own part in fighting fascism – in the Spanish Civil War.

The author of 1984 and Animal Farm has little to say about the first days of his journey, in his neatly typed diary or in the book. He walks 16 miles from Coventry to Birmingham in the rain. He admires the Bull Ring.

The purpose of his journey is to write about poverty and industrial Birmingham is booming. “It is only when you get a little further north, to the pottery towns and beyond, that you begin to encounter the real ugliness of industrialism,” he writes.

9,560 people are currently homeless in Birmingham. The annual rough sleeper count has risen from fewer than 10 in 2012 to 55 a night

More than 80 years on, central Birmingham’s futuristic buildings would be unrecognisable to Orwell but the ugliness of poverty starts early. “The city’s getting a facelift but you can see the cracks everywhere,” a homeless man tells me.

Research from the University of Portsmouth’s project A Vision of Britain Through Time has found the city is, in relative terms, worse off than in the 1930s. In 1931, its rate of unemployment was around 11%, similar to the national average. Today it has the worst unemployment figures in the country and also compares badly on child mortality and overcrowding.

A study by Shelter found 9,560 people are currently homeless in Birmingham. Meanwhile, the annual count of rough sleepers has risen from fewer than 10 in 2012 to 55 a night.

In the slash and burn of austerity politics since 2000, Birmingham has had the dubious honour of being – together with Liverpool – the city in England worst affected by local authority cuts. Even as it mourns the death of a homeless man, the city is already facing the loss of another £10million – to come from a crucial lifeline for homeless and other vulnerable people.

Average age of death is 43 for a woman and 47 for a man

A cold 20-minute walk from John Bright Street is SIFA Fireside, a place as warm as its name, where 150 people a day queue for a cooked breakfast. “We’ve noticed a big rise in people coming to us,” says Lynn Evans, the charity’s resettlement manager.

Chiriac Ionut wasn’t known to the project but Lynn explains jobseekers from Romania are often not entitled to housing benefit so Chiriac could have struggled to get a hostel place. “The shocking figure that sticks in my mind,” she says, “is that a street sleeper’s average age of death is 43 for a woman and 47 for a man.”

Labour MP Jess Phillips is fighting the new round of cuts, alongside charities in the city. “This next £10 million in cuts will hit refuges, young homeless people with nowhere to go and people with crippling mental-health problems,” she says. “I've never known the city be so full of rough sleepers but in a year’s time, if the Government don’t hear us out, there will be twice as many.”

In the meeting room at SIFA, The Dissenters, a homeless band, are playing Bad Moon Rising, its chorus ‘Don’t go round tonight, it’s bound to take your life’ striking a haunting note. Guitarist Pete Higgins apologises that his fingers are numb from chemotherapy.

Singer Chris Swain says he knows of two more homeless people who died, one on Christmas Day – “they just didn’t die on the street”. He says he would never sleep in the city centre. “I’ve been urinated on, just for being on the street,” he says. “It downgrades you. You have to walk around in the wet and cold.”

Harmonica player Darren Vaughan, 51, has spent months sleeping rough in woodland all over the Midlands. “Sometimes not being homeless is very hard,” he says. “I call it banging your head up the system.”

The help these men need is getting harder to come by. The term ‘Orwellian’ is used again and again to describe the modern benefit system. Cuts to local services mean there is less support. “It’s not just benefit sanctions that bring people here,” Lynn says. “It’s often just total bureaucratic failure. It’s also zero-hour contracts, low pay, bad landlords and cuts to services. There are so many pressures.”

As you travel northward your eye, accustomed to the South or East, does not notice much difference until you are beyond Birmingham. In Coventry you might as well be in Finsbury Park and the Bull Ring in Birmingham is not unlike Norwich Market and between all the towns of the Midlands there stretches a villa-civilization indistinguishable from that of the South. It is only when you get a little further north, to the pottery towns and beyond, that you begin to encounter the real ugliness of industrialism – an ugliness so frightful and so arresting that you are obliged, as it were, to come to terms with it.

Orwell on Birmingham, Road to Wigan Pier

Had Orwell visited Birmingham today, it’s easy to imagine he would have admired not just the new Bull Ring but the city’s famous guts. Even in times of chilling populist rhetoric, the reaction to a homeless Romanian man’s death has been to bring a city together in defiance. Mass protests against cuts have been held. Impromptu projects giving out hot meals have been inundated by volunteers. Against the brutal assault of austerity, Britain’s second city is tending its humanity like a flame.

Orwell writes of a woman seen from the train window – an image that haunts his memory: “She knew well enough what was happening to her, understood as well as I did how dreadful a destiny it was to be kneeling there in the bitter cold.”

As I get on the warm train it is below freezing outside and news is breaking of a homeless man in Liverpool who has died overnight.

What the numbers say

Your story

If you live in any of the places mentioned in the Wigan Pier Project and have a story to share, please get in touch.

You can contact us via wiganpier2017@mirror.co.uk tweet us at @WiganPier80 or write to Wigan Pier Project, Daily Mirror, One Canada Square, Canary Wharf, London E14 5AP

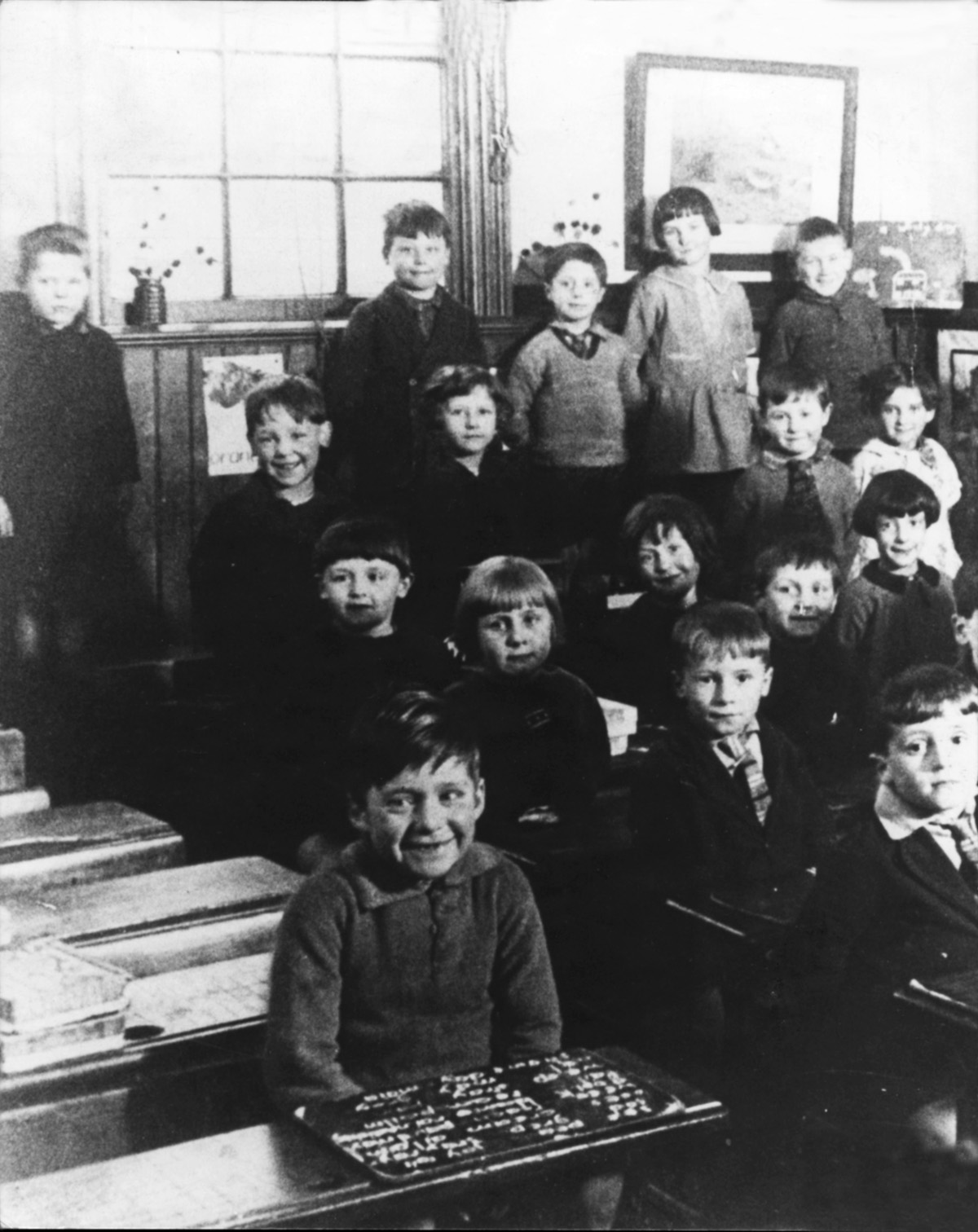

From the archives

Fascinating photographs from the Mirror archives showing what Birmingham looked like when Orwell visited

For housing advice

For housing advice

For general advice

For general advice

For foodbank help

For foodbank help

For help in work or out of work

For help in work or out of work